It took the tragic jolt of Sita’s passing for this thought to crystallise. That In some exceptional people, looks embody the soul and razor sharp mind. So it is with Sita, Sitaram Yechury. His smile, charm, chuckle, razor sharp mind and gaze laced in past years with a tired sadness, embodied him, the man, the political ideologue, the crafter of coalitions and the general secretary of the Communist Party of India (Marxist) –the CPI (M). All positions he bore as lightly as his cotton-khadi shirts and kurtas, with not an iota of oomph. In and out of Indian Parliament, the Rajya Sabha, his interventions are historic treasures, that go back a decade. His speeches, two of which I recall here, one on saying adieu and paying respects to marshals in Parliament, when he told his colleagues in the upper house, how the dignity of their labour must be protected and they should not be put on contract. Another in 2017, was on the debilitating phenomenon of the cow vigilantes when he demanded, through a full-fledged speech in Parliament, on July 19 that “private armies of “gau rakshaks” should be banned by both the central and state government order. The speech had been made during a short duration discussion rising out of reported increase of lynching and atrocities against minorities. [1]

When, as is our want, as chroniclers of the times, we are pressed to pen our words, our tribute to this special man, leader, father, partner, comrade, thoughts crowd in, yet words refuse to flow in cohesion. Exactly seven days on, after September 12 when we were numbed and chilled to the core as the 3.03 p.m. news crept in, I attempt this piece. Cringing in the knowledge that so much of meaning has already been written.

What more, then, will I have to say?

I will begin this homage, or tribute with this then, sharing (s) from last Friday and Saturday when we collectively bent our heads and grieved first at Seema-Sita’s Vasant Kunj home laced and lined with gracious scented white blooms dotted with the defiant communist red and then, the next day at the Gol Market party office, AKG Bhavan where we had spent so many hours with Sita and other comrades, over the years. I did not just meet Sita there though, over decades. It was most often at the Sahmat daftar, first the one at Vithalbhai Patel house (8 VP house), then at 29 Ferozeshah Road and the last several times at 36, Pandit Ravi Shankar Shukla lane, adjoining the All India Kisan Sabha (AIKS) office. His visits for lunch and pow-wows with close comrades were intimate and friendly and those of us who could get a few minutes –often more—of his time—chatting with him on issues of grave importance, one on one, were lucky. The depth of his understanding of the ever morphing forms of ugly communalism-translated into a bitter abdication by the state and violence and misery for hundreds of thousands of our own, Muslims, made common cause with the work that we– Javed and I –have dedicated large parts of our working lives to robustly counter. His unwavering support of this work, through thick and thin, through better times and bad, was and is special yet part of the support that the party he joined in 1975 (he had joined SFI a year earlier) always offered and has given us. Deep bows and Lal Salaam Comrade!

Sita’s was an unwavering commitment to socialism and communism, his sharp reading of history matched his dedication to the soil of this land, the many layered and many flavoured freedom struggle that ousted the British. More than anything else it was his layered and complex understanding of India’s agrarian crisis, the issues of labour organised and unorganised and for me especially, social justice that must come with a critique of communalism and a stand against caste that were fascinating. His admission, somewhat reluctant, of the urgent need of the party and left theorists to really factor in caste and issues of social justice to a class analysis goes back to 2001 or more. I was privileged to be among those who, with support from Sahmat, drew in all parliamentarians to support the cause of Dalits at the Durban UN Conference. That year, on August 31– September 4, when the World Conference Against Racism, Racial Intolerance, Xenophobia and Related Intolerances (WCAR) met in Durban, the first time since the discriminatory and centuries old regime of apartheid was overturned (in South Africa, early 1990s, formation of the first democratic government in 1994) through much sacrifice and struggle in that country, another group of subordinated peoples, discriminated by descent and occupation, forcibly segregated by tradition and religion from access to common resources, Dalits from South Asia, made their voice heard before the international community. The demands, sharply contested by the right and also other “mainstream intellectuals who rebutted claims on the matrix of sociological definitions” was clearly that that caste-based discrimination, which amounts to descent and occupation based oppression, segregation and exclusion be recognised as a distinct form of racism. A distinct form of racism, because it amounts (and has for centuries amounted to) to the denial of basic human rights based on prejudice, discrimination or antagonism and is justified by well–entrenched beliefs about high and low, superior and inferior.

The contrasting stance of India and Nepal are illuminating. As I wrote in Communalism Combat (April 2001, Hidden Apartheid). At the preparatory meeting for the WCAR, on February 19 in Tehran, the Indian government (NDA-I under Atal Bihari Vajpayee) made its stand clear — introducing caste into the ambit of the WCAR at Durban would amount to diluting the concept of racism. The government delegation was represented, among others, by then attorney general, Soli Sorabjee. More significantly perhaps, government spokesmen stressed that the problem of caste was an ‘internal’ one and therefore out of the purview of the UN. In stark and sharp contrast to the Indian government’s position was the Nepal government’s candour on the same issue, confronted as it was, then, with assertions of Nepali Dalits who account for not less than 15 per cent of the total population. The government of the only Hindu kingdom in the world openly admitted that caste is the source of acute discrimination and segregation within Nepal. This, it held, was a serious issue that falls under the theme of the forthcoming conference and should, therefore, form part of the official deliberations at the WCAR at Durban.

The idea of this recollection is not to lay down the rich nuances of that debate, that –given the Rashtriya Swayam Sevak Sangh’s (RSS’) and Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) stance on caste even turned nasty for some of us supporting the Dalit demand – but to emphasise the readiness of a man of Sitaram’s intellectual and political acumen to engage with the challenge. A challenge that the demand posed, even to the organised left, the CPI-M, that has been accused of, historically and to date, ignoring the issues of caste oppression and inclusion.

Sita participated in the pre-Durban conference deliberations and lent his voice and support to the Dalit movements’ demand that was essentially attempting to take the issue of caste–based discrimination to a global forum; to solicit international condemnation of caste–based discriminatory practices and support for the struggle against it. Let’s not forget that caste based discrimination, legitimised for centuries through scripture and followed in practice by notions of high and low, superior and inferior, pure an impure. Even 77 years after independence, the problem persists. The Dalit condition, which was the result of such a pernicious theory, is the outcome of a narrow and hierarchically powerful assertion of race by perpetrators of this condition and not the other way around. It is not the metaphor of race that was being invoked but the metaphor of racism, which was the outcome of the misplaced metaphor of race. This Sita understood and as late as five months back, in early 2024, publicly articulated. The need for the organised left to be really seen as a serious political party that regards class as much as caste (and communalism) as the root of Indian oppression. For us at Communalism Combat, too this (journalistic) journey has meant deepening our understanding of how communalism (and majoritarian proto-fascism too) cannot be theoretically understood nor soundly countered or overcome without factoring in, or also battling caste.

The core of our conversations and parleys –Sita and mine–of course always dealt with the work we had undertaken, at great risk and challenge since 1992-93. First in the publishing (in book form) of the Srikrishna Commission Report on the Bombay communal riots of 1992-1993 (copies of which we sold at Rs 60 and 90 to ensure wide readability and availability). This journalist-activist action was born of our realisation that, most judicial commission reports that dissected the causes, build up and fallout of targeted communal violence post-Independence, are documents of legal-political importance that need to influence institutional memory to build in preventive and other measures to ensure that such violence does not periodically – and with more vicious intensity-repeat. For the past 32 years since then, a major personal academic and journalistic endeavour of mine has been to continually engage with these documents, ensure wider reach and availability, a task I am still currently engaged in. As editor of the CPI-M’s People’s Democracy, he was the first one, instrumental in ensuring that independent voices like us contribute to the party organ. Sita needed to fight numerous internal battles to allow me and other contributors the space to write what we wanted in PD in the manner we wanted to. But, in his own inimitable way, persuasive yet dogged, he got his way. This relationship has paved the way for a unique equation between me, a journalist activist academic and the CPI-M that is rare, precious and unique. Sita and Rajen (Rajendra Prasad) first, and then of course comrade Brinda and so many others have ensured that this relationship has been enduring. Communalism Combat (published from August 1993 to November 2012) and most particularly in the work of Citizens for Justice and Peace, post Gujarat 2002 is something that was more than close to Sita’s heart. It was an engagement that he saw as vital for the reassertion of the Constitution, a visionary document that arose out of India’s struggle for freedom. Not a day or month passed in that rich yet fractious battle (that still continues!) with a rogue state and its unaccountable functionaries, that Sita did not have his ear out for us, watchful of our predicament, support unconditional, during vilification and even incarceration. With Rajen and Sahmat in the tiny vibrant office spaces, often, and then at his Gol market office too, long elaborate discussions on the intricacies of our legal battle for accountability and reparation took place. The fact that we at CJP, always centred Survivor Voices in this battle, ensuring that the names of those who had loved, lived and lost their closest ones in the brute perpetrated violence is something that Sita deeply understood and empathised with. He met and interacted with the Survivors who bravely shared their tales and his words, his presence, renewed their faith. In not just their battle for Justice (that has remained only part fulfilled) but in the idea of India itself and the Indian Constitution too. How else can a mother who has lost her only son, another who has seen her sister and daughter raped before her eyes, a wife who lives sleepless with guilt of her dear husband’s death, a former parliamentarian not just hacked to pieces but his reputation smeared too, dare to live on? It was the warm, firm support of a man like Sita – among so many others – who met them, had the patience to listen, who spoke of the issue boldly, even when it became politically non-expedient, that meant we were not completely alone. Post September 3, 2022 when I visited Delhi after my release from jail, one of the most memorable moments of my life – one that I cherish close to me – was the lunch Rajen and colleagues organised at Sahmat – when, within minutes of my reaching, the general secretary of the CPI-M, Sitaram Yechury came by to hug and salute, with partner and fellow journalist, Seema, and soon, another Polit Bureau member, Brinda Karat, followed. Unflinching has been the support and personal respect and affection that I have been fortunate enough to receive. Hundreds of letters that I received from women activists and comrades of the AIUWFP (All India Union of Forest Working Peoples) and AIDWA (All India Democratic Women’s Association) while interned at barrack 6 of the Sabarmati Mahila Jail, Ahmedabad were an immense source of succour and strength.

Yes, it was the minor details and sheer expanse, Sitaram’s grasp on constitutionalism and parliamentary procedure, the irreverence of authority and most of all Sita’s playful charm and chuckle, all of this, that made the time spent with him, something you (silently) tuck away. To savour for another day. For the way Sitaram matched words with ideas, wove in culture and history, shared this with the ease of complete camaraderie made the conversations special.

Words often desert us when a near one passes. There is shock, disillusion, need to collectively grieve and share and then the inevitable clichés. So let me share more of some and all of these with you from September 13-14 in New Delhi.

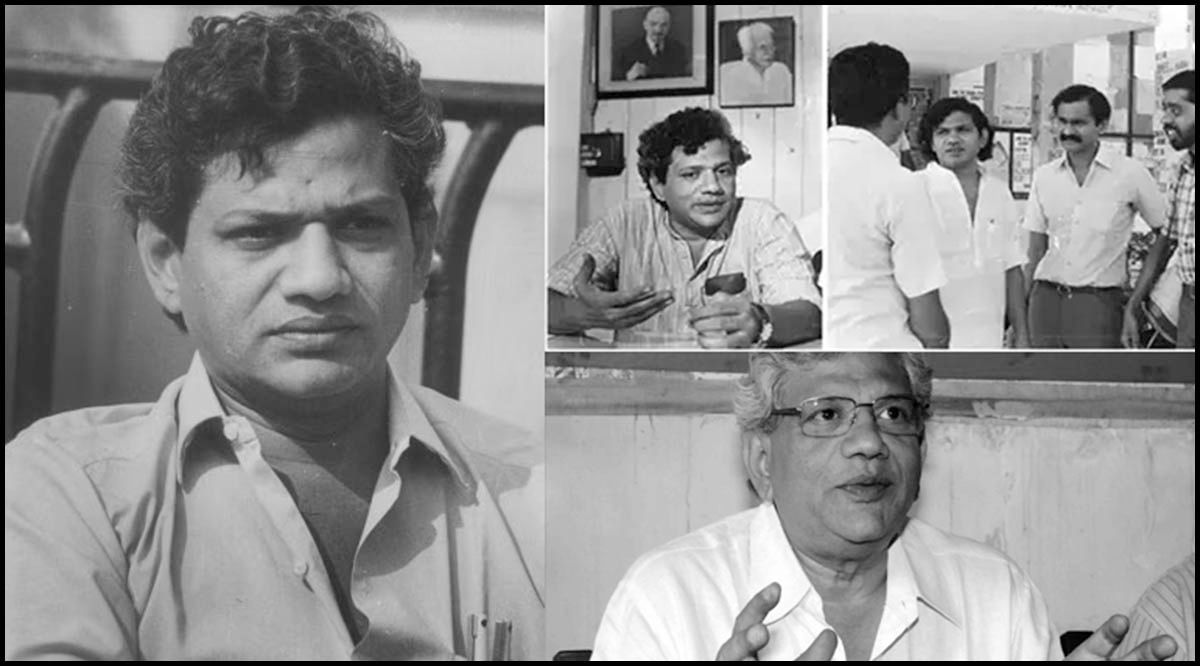

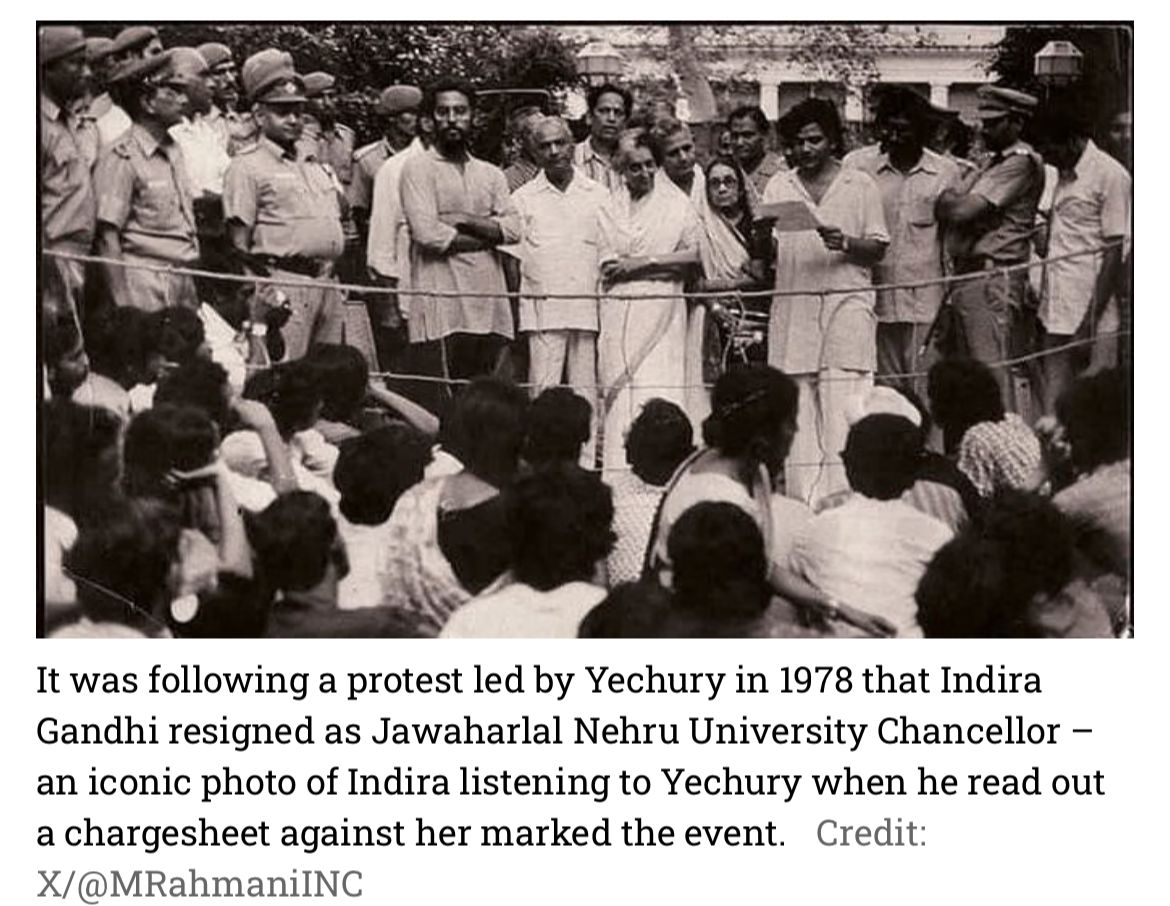

The elegance and beauty of the flower malas and garlands strewn on the staircase up to the first floor home matched the fragrance of goodwill, care and grief within. They had been handpicked by Kanishka and Vertika (of the Prasad-Chopra-Chaturvedi clan) from the flower market at Seema’s special request. Sita lay before the beautiful, large poster of the original blockbuster, 1949 film, Andaaz with the triangular cast of Dilip Kapoor, Nargis and Raj Kapoor, directed by Mahboob Khan and the songs by Majrooh Sultanpuri. This larger than life poster adorned a bright red wall painted for Sita as a special gift by partner Seema to and for her communist humsafar and love, Sitaram. Kahwa and then tea was served graciously to all (daughter Akhila, son Danish and daughter-in law Swati) as we sat and shared the moments of loss as Pinarayi Vijayan, chief minister of Kerala, much later Chandrababu Naidu, chief minister of Andhra Pradesh (remember Sita was the Andhra boy who entered Jawaharlal Nehru University-JNU and became the student union president in 1978) and so many other political figures (even from the ruling dispensation) paid homage. Comrade Brinda Karat was staunchly by the family’s side both last Friday and through the weeks of care at AIMS, Delhi where he had been admitted on August 19 with a pneumonia like infection. There was disbelief and loss and as always a shared camaraderie and many precious conversations.

The next day at the party office was different, yet similar. Here was a different homage, formal, rich with the presence of so many special names from the political and intellectual firmament but it was also one large family. A large, large gathering from the morning till 3 p.m. when the final march began from AKG Bhavan to 14 Ashoka Road, the CPI-M office and finally to AIMS where Sita said goodbye must have touched 25,000. Young people, party affiliated and not, were there in significant numbers. It was not the numbers however but the shared common emotion of loss and belonging that were tangible. District committee members of the party from states across the country recounted how this man, who represented this party and organisation to the world (Sita headed the International Department of the CPI-M) and within India, across regions who spoke Bengali as much as his mother tongue Telugu, Malayalam, Hindi-Urdu apart from fine English was one of them, a comrade who had no airs, who was not just accessible but understood the value of each woman and man in this giant structure. To feel this tangible quality of what Sita was that day in the hot and sweaty mandap outside Gol Market is something I do not think one will see too often, again. His close colleagues Muralidhar, SN, yaar NK Sharma stood some distance away bewildered, unable to face the loss. Danish his second adored son quietly went up and paid homage to his father in the office, the office of the general secretary of the party, where Sita had sat, after some tussle and pulls, since 2015.

Sita’s personal life with Seema in their home and beyond reflected the openness and flexibility of him as a person, the staunch communist ideologue with a generous and practical pragmatic bent that deeply believed that the rich nuances and diversity of India’s coalition politics was not just a pragmatic necessity but possibly, the best way for an inclusive and representative government. His mentor, the wily Sardar of the party, Harkishen Singh Surjeet, groomed Sita well in the dos and don’ts of building consensus. We are too vast, diverse, bonded yet different for any structural rigidity to successfully bind us. The bonds that bind must be – like at the time of India’s struggle for freedom – bows of common cause with arrows that focus on all kinds of oppression, gender, caste and communal driven. These too must evolve with the times and technologies of the day. Language of the young laced with the rich learnings of our positive past is something that Sita respected and we must too.

Not a day has passed since that day, September 12 that I have not thought of Seema, and Sita often. It is a bruising sort of pain. Especially when I think back to that day, April 22, 2021 when the family lost their elder son, Ashish (Bhiku) Yechury to Covid-19. The grace and stoic courage with which he, Swati, Indrani Mazumdar, Seema, Akhila and Danish bore that loss is rare to see. It was the same grace that was evident on September 13-14. Bonded again in quiet and dignified grief, one heart-breaking moment was when Indrani said to me, “how similar Sitaram and Bhiku were and now they are both gone.”

His dear wife and life partner Seema, a professional colleague and friend will bear the loss with her customary courage and shrugging, biting humour even as she tears up in unbearable grief. The loss will remain a constant void. The dignified threads of love and sharing with all three children will mitigate the difficult passing. Apologies for this additional dose of sobriety and sadness but it is impossible to pen this piece without reflecting and sharing how unfair it has been, for the Chisti-Yechury-Mazumdars to live through this twice. The loss and pain of a loved one’s aching departure.

For Bhiku, at Delhi’s Sunder Nursery, loved ones have dedicated benches to their beloved and lost ones (benches trigger nostalgia, anticipation and also, an inscription becomes an epitaph of belonging). Here we have, this family who has dedicated two benches to “beloved Bhiku” (Ashish Yechury). One of the inscription reads: You left us bereft but with much to discover of the season and the times captured by your camera… And the quirky touch that remains forever you. The second one, also dedicated to Ashish Yechury, ends with a poem by Nigerian poet Ijeoma Umebinyuo: “So, here you are too foreign for home, too foreign for here. Never enough for both.” Both are, as I said before, in the loving memory of Ashish Yechury.

And then I think, in how many Indian and world cities, Delhi first of course, will benches be dedicated and inscribed to Comrade Sitaram Yechury? His footprints left imprints near and far, and in each of these locales, to that bench that will inscribe, deep affection, loss and love at his too early parting.

Fare thee well comrade Sita, Au Revoir.

Teesta