Turmoil, Triumph (of sorts) and Tyranny In a Decentralisation Platform Marred By Caste Oppression

“Ear to the Ground”, The AIDEM’s unique series that captured and presented offbeat ground-level reports that went beyond the run-of-the-mill narratives of mainstream media is back with this riveting “time-travel” account on a grassroots democracy initiative that went awry in Tamil Nadu’s Madurai District. This report is by renowned Malayalam writer and journalist KA Beena, who has systematically followed and analysed the processes of decentralisation in India, across very many States. This account from Tamil Nadu is certainly an eye-opener as it unravels manifold nuances and complexities that have characterised decentralisation initiatives in India.

I am with two people who thought they could celebrate the tunes of democracy on an egalitarian platform, but ended up as human wrecks in the sphere of public life. Two individuals who were pushed and pulled by other people and their trenchant manoeuvres leading to a dramatic downfall. The cumulative impact of all this was such that they perforce became part of a social narrative which they could not control or dictate. Or rather, a narrative in which they had absolutely no role when it came to fulfilling the democratic aspirations they had so fondly nurtured.

One of them is Baluchami. He has a bearded face and a frail physique. His posture betrays the depths of his sorrow, with his head bent forward. The other is Periya Karuppan who strives with all too evident pain and discomfort to prop up the weakened left side of his body afflicted by a paralytic stroke.

I first crossed their paths 10 years ago at Usilampetti, some 40 km away from Madurai in Tamil Nadu. Prior to that, Usilampetti to me existed just as an imaginary Tamil village popularized by the iconic A.R. Rahman song Usilampetti penkutty muththupechh…. (Girl from Usilampetti, here’s some sweet talk for you …). But then I actually reached the village, some ten years ago. I had a more focused destination in the village, two rural hinterlands that went by the names of Keeripetty and Papapetty.

Like so many other rural hinterlands across India, even the word development was not properly heard at Keeripetty and Papapetty. I was then working on my book “Hundreds and Hundreds of Chairs”, (Nooru Nooru Kaserakal in Malayalam) and as part of my research, I had to study the impact of reservation for women and Dalits in Panchayati Raj institutions. The effort was to find out how far reservation has helped in terms of opening a pathway for these marginalised sections of society and how far they have got integrated into mainstream society. It was George Mathew, Director of the Institute of Social Sciences, New Delhi, who told me that my research would be incomplete without studying the two villages as well as Baluchami and Periya Karuppan. It took me to the villages dotted by sugarcane plantations, arid land, and grasslands where cattle grazed.

It was here that I met Baluchami and Periya Karuppan. They were not just ordinary men. At that time, they were celebrated as real gatekeepers of Indian democracy, who sustained the democratic polity and imparted energy and vigour to it. They had actually garnered the attention of the entire nation through their service.

But the larger political and social background has to be recounted before we get into their story. It was in the year 1993 that the then Congress government at the Centre enacted the Panchayati Raj rules to empower women and Dalits by amending Articles 73 and 74 of the Indian Constitution. This system of Reservation came into force in Tamil Nadu in 1994.

However, there were strong protests against this decentralisation move in the southern region of Tamil Nadu. Not just that, the upper caste people tried their level best to ensure that no presidents were elected for the panchayats of Keeripetty, Papapetty, and Naattamangalam in Madurai district and Kottayikachiyenthal in Virudhunagar district for 10 years between 1996 and 2006. The Piramalai Kallar community who belonged to the Other Backward Class were regarded as the dominant “higher caste“ group in the region. And, the Dalit groups were known by the names Pallar and Parayar. Incidentally, the Kallar community could never accept the Dalit groups being brought under the ambit of reservation.

The Kallar community could never accept the concept of Dalit groups being empowered and given access to elected positions in local self government. Curiously, even the Dalits were unwilling to change their belief that they were destined to slog for the upper caste communities. The upper castes went all out to make sure that an election never happened in the region.

They did their best to sabotage the poll process by fielding their own subordinates belonging to Dalit communities in elections, thereby blocking the chance of others. They adopted a modus operandi wherein a dependent Dalit worker was compelled to submit nomination (a Dalit woman submitting nomination for election was unthinkable then), for the elections. However, while getting his thumb impression on the nomination papers, he was also asked to give his thumb impression on another piece of paper, which happened to be his resignation letter.

On the day of the election, a Dalit chosen by the upper caste people would be elected panchayat president, and the very next day, he would submit his resignation. Naturally, the authorities would summon the president and seek an explanation from him as to why he put in his papers. And, the most common answer would be, “I am scared” or “I have no time”, or “I can’t live without a job”. Subsequently, the authorities would notify another election. This rigmarole repeated in this region a mind boggling 19 times.

Those Dalits who made bold to file genuine nominations were done away with physically or marginalised and moved out of the scene by ostracizing them. These four panchayats thus brought such a bad reputation for the entire region that the judiciary and the media were compelled to intervene. In 2006, Chief Minister M. Karunanidhi, who himself considered these villages symbols of shame, issued strict orders that elections should be held in all the four panchayats.

Some developments of the year 2000 were significant in the context of this order. In 2000, a Dalit named Poomkudiyar had come forward to contest the polls. However, after submitting his nomination, he fled to Madurai, fearing for his life. Baluchami’s elder brother had assisted him in this flight to safety. As a result, along with Poomkudiyar’s family, Baluchami’s family too had to face ostracization. Outraged at the candidature, the Kallar community destroyed Dalit homes, and one of them happened to be Baluchami’s. It was a turning point in his life. Having lost everything, he decided to contest for the seat reserved for Dalits.

In the 2006 elections, Baluchami submitted his nomination. However, he too was forced to flee to Madurai where he settled down. He was supported by the Communist Party of India (Marxist). The party helped him live undercover. On being alerted by the CPI(M), the then District Collector T. Udayachandran visited the village and met the upper caste people and warned them of stringent action if they went ahead with their ways. The Collector’s warning did have an impact and the Kallar community desisted from fielding their candidate. Baluchami was elected president. The government as well as the CPI(M) gave him tight security. All this, cumulatively, became a big blow to the upper castes.

Still, the social situation did not change dramatically in the village. The Dalits were even scared to openly meet Baluchami, though many of them got one administrative help or the other using the Panchayat President’s good offices. The next four years, Baluchami governed Keeripetty panchayat with police protection. Once his term ended, there was no more police protection. Though he contested all elections that followed, only Dalit candidates supported by the upper castes won.

I went back to the region recently (in 2024) ten years after the end of Baluchami’s term as panchayat president. I found him crestfallen. His family was now being supported by his wife Rasamma who is employed under the rural employment guarantee scheme and works as a daily wage earner at construction sites. No one calls Baluchami for work nowadays. His daughter Jayabharati, along with her three children, has returned home, reportedly unable to endure the torment inflicted by her husband who is a heavy drinker. His son Jayakumar is a daily wage earner.

“We used to have a comfortable life. We had enough cows. We never faced cash constraints. That was when elections were announced, which upset our life,” Rasamma recalled.

Jayabharati had more to add. “My ambition was to become a lawyer. I used to be a good student. But our dreams were shattered after my father became panchayat president. We used to wonder why he stood for elections. We lost everything because of that. We are able to survive because of the job guarantee scheme and ration supplies. We had to sell our house to fund my son’s heart surgery. We now live in a relative’s home,” she said.

“The Dalits of this region had some material gains after my father became panchayat president. We now have the freedom to wear chappals in places where Kallars live. Earlier, we had no access to those places. Also, it was after father was elected president that the Dalits could use shawls. It was he who gave the Dalits of this region a sense of identity. However, we are still at the receiving end. While fetching water from the public tap, we have to keep our vessels last. We get our share of water last. This is what I get for being Baluchami’s daughter,” she said.

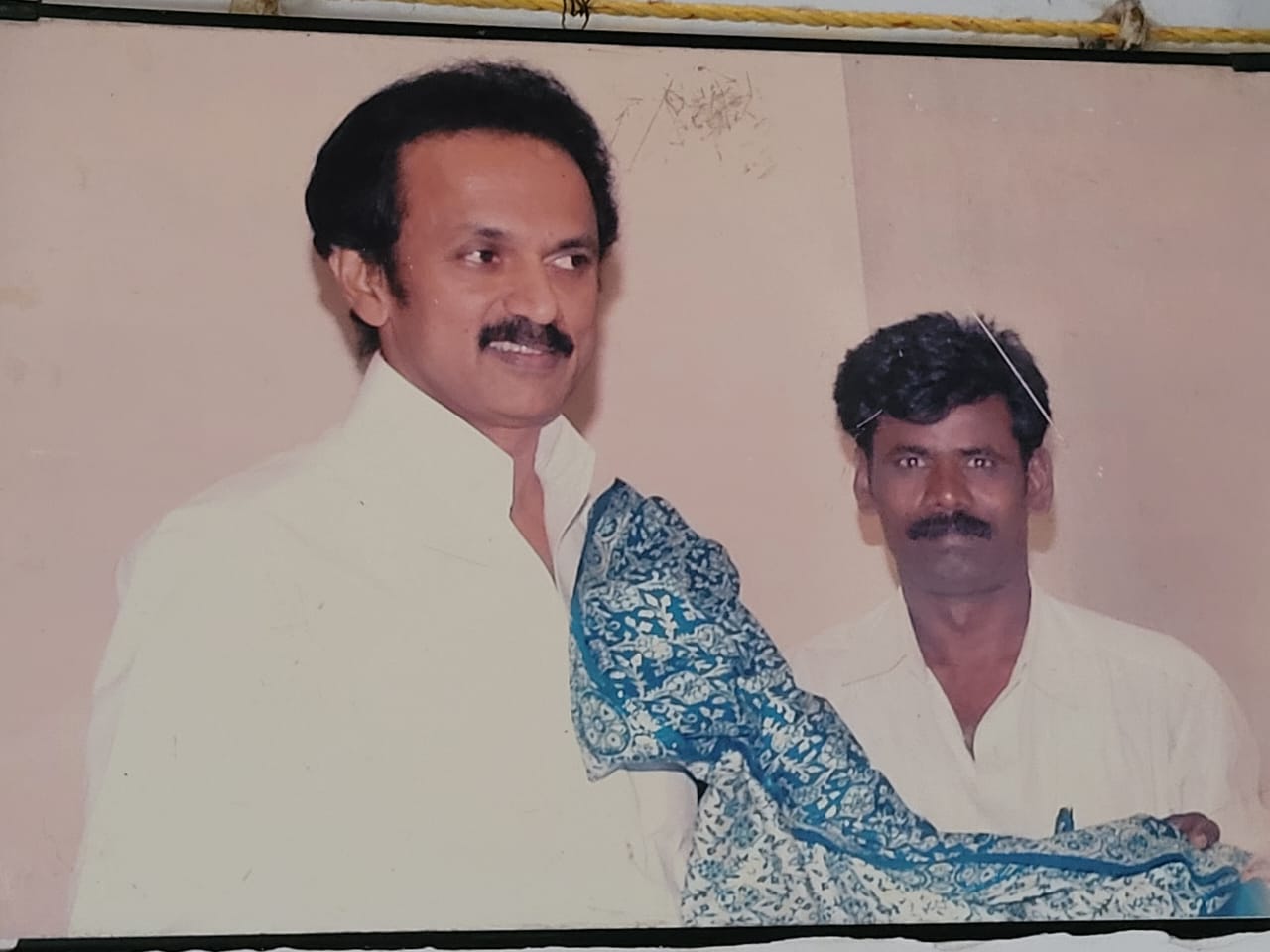

On the wall of Baluchami’s house are mounted photographs of him receiving an award from MK Stalin, the current Chief Minister of Tamil Nadu, besides the pictures of former Chief Minister M. Karunanidhi and CPI(M) leader G. Sudhakaran. While Baluchami got sidelined for contesting elections defying the diktats of the upper castes, it was different story of desperation and defeat for Periya Karuppan who agreed to be a rubber stamp panchayat president for the upper caste people and yet could not ensure a smooth or upwardly mobile life.

When I met Periya Karuppan during my second visit to the village he was desperation personified. One could not call his house a house. It was a dilapidated hut, not fit for dwelling. The kitchen was a room that had disintegrated almost to the last few bricks. His wife and daughter used to cook food on the road. The one-room hut could collapse anytime. Firewood was kept beneath the cot used by Periya Karuppan to keep it safe from rain.

“Chief Minister Stalin passed by Periya Karuppan’s house to attend the grama sabha of Papapetty at Ochandammankovil on Gandhi Jayanthi day in 2021. However, Periya Karuppan was not invited to the function. Even I was not allowed inside,” said Baluchami. However, Periya Karuppan intervened and said, “I should have contacted Chief Minister Stalin over the phone. Perhaps, he was not aware of my situation”.

Periya Karuppan sleeps below the photograph of former Chief Minister M. Karunanidhi. There is also a photograph of him with Chief Minister Stalin on the wall. His wife finds money for his medicines by working as a daily wage earner. His daughter Sharanya is a widow with three children, and they all live with him.

Periya Karuppan says he enjoyed special status while he was president of the panchayat. “My thumb impression was enough for many people to get their things done. I helped several others find employment. People gave me money for my daughter’s marriage, besides constructing rooms for policemen who were deployed for my security,” he said.

But once he relinquished office, members of the Kallar community went to him with an account of the money that they had spent for him. Interest over penal interest has been imposed on this sum. He is now indebted to them for a large sum. “Both of us have applied for pensions. We will apply again now,” both Baluchami and Periya Karuppan told this writer.

As I left Usilampetti, contemplating how these two individuals manage to survive and live, still believing in a governance system and its promises such as people’s welfare, equality, and justice, I found myself overwhelmed. Indeed, the twists and turns of democracy are difficult to comprehend.

What exactly had happened in the village? After 2011, who wielded authority in the panchayat? Will the Dalits who govern the panchayat as rubber stamps of upper castes really be able to enjoy the benefits of reservation? How many living martyrs like Periya Karuppan and Baluchami should the Dalit communities see and endure before these poor people can secure their rights? I realise I have no definitive answers to these searing questions.