Transvanguardia: Moving Beyond Time And Geographies Through Art

In a sense, a return to skill of the past, after an age of conceptual based art, as it happened with art in the Occident and subsequently in the Orient, was inevitable.

Back in 1979, Italian art critic and curator Achille Bonito Oliva wrote an introduction for an exhibition he organized in the town of Genazzano, (a town and commune in the Metropolitan City of Rome). Titled Le Stanze (The Rooms), the show gathered a small group of young painters whose practices seemed to have revived the Expressionist painting at a time when Conceptual art ruled art tendencies to its full potential. In order to describe their work, Oliva coined the term Transavanguardia, or trans-avant-garde, announcing the beginning of an international phenomenon which took place in the late 1970s and throughout the 1980s, and became one of the most influential movements of Post-war Italian art along with Arte Povera.

Francesco-Clemente at the Rubin Museum, Gallery View

Francesco-Clemente at the Rubin Museum, Gallery View

“In many ways Transavanguardia became a way of dissolving the linear demarcations of the art movement and resorting to a move freer way of moving back and forth, refereeing to history as well as addressing the hysteria of the ‘new’ –the here and now,” says Oliva who is visiting India and curating the exhibition, The Grand Italian Vision, from the Farnesina Collection. The exhibition that is currently on display at the Bikaner House in New Delhi, features a handpicked selection of 70 pieces of painting, sculpture and photographs and even a few small sized ‘installations’ of handmade objects.

“In my belief, art is a massage for the atrophied muscles of collective sensibility,” says Oliva. Put very eruditely by Oliva it is best described as the ‘freedom to move forward but also move back in time and reference the past. It is thematic rather than linear’. This ties in with the Indian approach which looks at time as cyclical rather than linear and hence things recur but in a different way each time. We see this in art, and more so in India and Asia where the reference to the past is a constant where many of the Modern artists talk of the aesthetics of the Rajastjani, Persian and Mughal miniatures, the Warli painting, the Madhubani and the Kalighat Pats in the same breath as they embrace the Modern and what is now called the Contemporary.

However before we address the commonality between Indian and Italian art we need to better acquaint ourselves with the Transavanguardia movement. To revisit the movement and its impact on art history, we have to go back to the 1980s. At the Venice Biennale, of that time, five prominent artists were showing under the Transavanguardia movement, that Oliva curated, and they stood out—their artworks drew attention for their diverse styles and common vision. They relied on strong narratives, painters Francesco Clemente, Enzo Cucchi, Sandro Chia, Mimmo Paladino and Nicola De Maria—the artists re-created a strongly expressive language which oozed in vibrant colour, the depth of space, the passage of time and the freedom of technique.

“The conceptual art movement was dominated by artists from the United States and the Transavanguardia movement brought the focus back to art that celebrated the act of creating with one’s hands of painting, and sculpture,” says Oliva.

That 1980s exhibition at the Venice Biennale, gave these individuals an opportunity to compete for a place on the international art market, dominated by significant figures and tendencies from. The paintings they produced offered a variety of personal interpretations of these notions: from Sandro Chia and his influence by Futurism and even Mannerism, the many materials of Enzo Cucchi, such as ceramics, wood, neon and steel, the almost childish quality of works by Nicola De Maria, Mimmo Paladino’s ‘totemic canvases’ and, of course, Francesco Clemente’s ‘haunting portraits’.

Disco Solare, 1989-90, Bronze Sculpture, Arnaldo Pomodoro

Photograph of Achille Bonito Oliva at The Grand Italian Vision, Bikaner House, New Delhi

Photograph of Achille Bonito Oliva at The Grand Italian Vision, Bikaner House, New Delhi

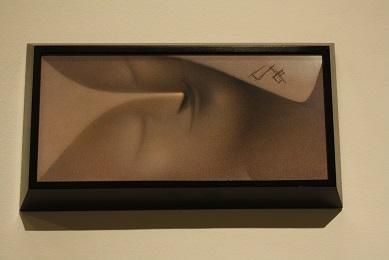

Opera Obliqua, 1997, Photography and Silkscreen printed on Panel, Gino De Dominics

Gallery View of the exhibition ‘The Grand Italian Vision’: showcasing the Italian Transavanguardia movement

Gallery View of the exhibition ‘The Grand Italian Vision’: showcasing the Italian Transavanguardia movement

Gallery View of the exhibition ‘The Grand Italian Vision’: showcasing the Italian Transavanguardia movement

Image Courtesy: Georgina Maddox

Interestingly Clemente, an Italian contemporary artist lived at various times in Italy, India and New York City. Some of his work is influenced by the traditional art and culture of India. He has worked in various artistic media including drawing, fresco, graphics, mosaic, oils and sculpture.

Born and raised in the farm lands of Morro d’Alba, province of Ancona, the artist Enzo Cucchi was an autodidactic (self-taught) painter. He was lauded in his early years even though he was more interested in poetry. He frequently visited poet Mino De Angelis, who was in charge of the magazine Tau.

The impact of Achille Bonito Oliva and his Transavanguardia Movement went beyond the borders of Italy, touching upon the borders of the US, Germany and even India. The Transavanguardia’s ‘quest to revive the potential of painting’ by drawing inspiration from the history of art itself, as well as classical mythology, popular culture and national symbolism, it went beyond Italy’s border along with Francesco Clemente. His works became a seminal part of Neo-Expressionism, further influencing the production of fellow creatives like Jean-Michel Basquiat and Jonathan Borofsky, David Salle and Julian Schnabel.’

Interestingly the exhibit entitled Francesco Clemente: Inspired by India, at the Ruben Museum in New York, displayed in 2014, was well received and showcased Clemente’s massive drawings with elements of installing the work to emulate a ‘Hindu temple’. The exhibition constituted a public space (like the main courtyard of a temple) marked by deep purple — occupied by the five huge drawings. There were four smaller meditative “niche” (grihas) spaces — filled here by sculptures. And finally, the “inner sanctum,” (the grabagriha) held 16 exquisite watercolor pieces and a portfolio of profoundly erotic watercolors, based on the erotic sculptures in Orissa (Odisha), India. Even more remarkable is the fact that the drawings, were made in collaboration with local artisans in Madras (Chennai) in the 1980’s. They include gouache on sheets of handmade paper, bound together by cotton strips to form billboard-sized drawings. The treatment to the paint is flat and the perspective is not of a western nature rather it emulates local pop and filmic poster art of the times.

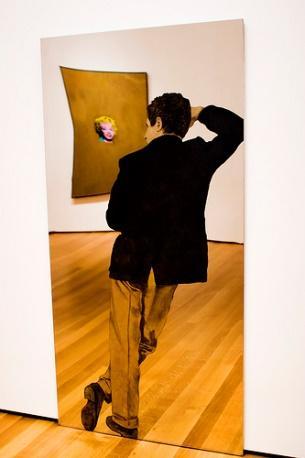

Michelangelo Pistoletto, Venus of the Rags, Installation, 1967

Michelangelo Pistoletto, Venus of the Rags, Installation, 1967

Michelangelo Pistoletto, Man with Yellow Pants, Paperwork, 1964

Michelangelo Pistoletto, with Disegnando il Terzo Paradiso, 2011

Michelangelo Pistoletto, with Disegnando il Terzo Paradiso, 2011

Image Courtesy: Google Arts and Culture

While each of these works by Clemente is interesting one cannot help but observe the dark humor of one of the image of the paintings. Here two nude male figures—one slightly lighter skin toned (clearly from the Occident) to the other (clearly Asian) examine each other by pointing at their orifices and body parts. It contains both a sense of innocence and a wicked bit of humor in it. We are told that Clemente was occupied with human orifice as receptacles of stimuli. He was also fascinated by aspects of Indians that he deemed as ‘mysterious, erotic, and spiritual’.

The themes and titles — Sun, Moon, Hunger, Two Painters, and Four Corners — reflect Clemente’s identification with many aspects of ‘traditional Indian painting’ combined with his own contemporary ‘Western angst’.

Mediterraneo, 1990-95, four black and white photographs, Mimmo Jodice Image: Georgina Maddox

Returning to Oliva’s current exhibition, at Bikaner House in New Delhi, one sees that works belonging to the earlier period are more in tune with reviving the sensibilities of Neo-Expressionism, paying ‘tribute almost’ to doyens like Heri Matisse, Picasso and even quoting from the classical art of the Italian Renaissance. One however notices that works belonging to a later period, (from the late 1990s to the early 2000s), there is a greater conscious sense of the global and of Asian nature; from the colours to the shape and forms. To summarize what Oliva is getting at through his curated exhibition, Transavanguardia addresses the fact that it is no longer possible to slot art into capsules of time and geography but it acknowledges that art is a product of the past, present and the future and hence it includes a mix of all these elements.

“Transavanguardia, invites society to share and to live together. All these movements represent a mosaic and this collection reflects that many things exist together and they are all equally important. It’s an invitation to peace.” says Oliva. Given the times that we live in, this value of art acquires political value. “It is no longer just art and it is a moment in world geo-politics,” he concludes.

Bibliographic Reference: