The Problem of Self-Determination: Challenges and Opportunities

An enduring problem

The ideal of self-determination is a problem that has faced mankind for long: From the League of Nations to the United Nations Organisation, in the aftermath of the Second World War, and beyond, to the current conflicts raging in Ukraine, the world has failed to find lasting answers to this vexing issue.

Groups and nation-states, as historian Ainslie Embree argues, are often seen pitted against one another in terms of language, ethnicity and political power. India has witnessed this problem since its independence from the British colonial rule. There has been no permanent solution, however, to the challenges that have risen in many parts of the country, including in Kashmir and the Northeastern regions. The state has often invoked the colonial era clause of sedition, but such draconian measures have not deterred periodical upsurges in centrifugal tendencies.

The rise of the all-powerful state

There has been negligible thinking and reflection on the claim/right of the all-powerful state to control and subjugate individuals, groups and communities in absolute terms. In this context, we may recall the cry of Antigone in the ancient Greek city state of Thebes who defied the might of the King Kreon. She remained defiant in support of her brother and her gesture a classic act of individualism.

Self-determination: Three historical phases

The trajectory of self-determination has essentially gone through three historical phases: the anti-imperialism of Lenin, [See ‘The Right of Nations to Self-Determination’ by V. I. Lenin, Feb.-May 1914] the Woodrow Wilsonian desire to break up empires into nation states, and finally, the balancing act of the U.N. The discourse on self-determination, as expressed in the world body, is often contrarian in character: While affirming the duties of states not to deny the right of self-determination, the U.N. also cautions against ‘self-determination as an invitation to disrupt the existing state system.’

How do we face the current crises of self-determination: in the family, the community, the nation and the world? This essay will suggest some answers. I shall argue that there is a need to depart from the established discourses based on Western modernity and seek answers from alternate epistemologies and world-views.

The right to choose one’s own destiny

According to the dictionary definition, ‘Self-determination denotes the legal right of people to decide their own destiny in the international order.. self-determination is a core principle of international law, arising from customary international law, but also recognised as a general principle of law, and enshrined in a number of international treaties.’

The right of self-determination has been a compelling drive throughout the world ever since man became aware of himself as a political being. An increasing number of people are involved in the process of choosing their destiny. As a result, they come in conflict with groups and nation -states.

We have not been able to find the magic wand, a permanent and lasting answer, to this vexing problem: How do we reconcile the search for unity with the equally important drive towards difference? According to a general view and received wisdom, differences are a source of weakness in all spheres of life; they cause delay and procrastination in decision-making; they present us before the outside world, hostile and invasive, as debilitating: unsuited and unsuitable to serve our needs in practical and pragmatic terms. Differences could arguably be celebrated in arguments and in academic life; however, they are best given up at the altar of power and expediency. Thus runs the reasoning.

In modern times, self -determination as a concept and practice has led to many political formations: The Soviet Union, the United States of America, the Organisation of African Unity, the United Arab Republic, the European Union and other regional formations like the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC).

Such groups and agglomerations have had their share of success and failures in the international domain. However, the larger question still remains: How shall we realise self-determination in the realm of the family, the community, the province, the state and the world?

Freedom, diversity and self-determination

Crucial to the philosophy and practice of self-determination, we may argue, is the notion of freedom of choice. But then, isn’t freedom itself a loaded term? Freedom is an attribute, a state of existence, or a way of life, political, moral and spiritual, which is invoked arbitrarily and used indiscriminately by most. For instance, a patriarch may invoke his freedom to oppress women just as an outright capitalist may do so to exploit the labour.

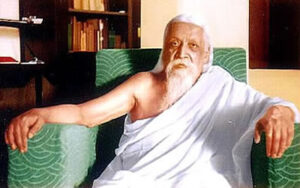

Critique of western modernity

In his powerful critique of Western modernity, Sri Aurobindo shows that a mechanical accommodation of interests, of mutual tolerance, based on the need for mutual survival is the inevitable corollary of Western modernity, which logically entails appropriation and colonialism. We see this manifest, he explains in his work War and Self-determination, in the clash between the ‘idea of liberty’ and the ‘idea of law.’ Equally does it manifest, he points out, in the ‘European statesman’s desire to teach liberty to the Asiatic’: the civilising mission of the West.

We must move beyond this limited notion, he concludes, to one that is based on mutual acceptance and mutual recognition. It is essentially the human failure to accord this recognition, on the basis of deeper affinities, that is the cause of war.

Multiculturalism

Viewed from this angle, we may see the reason as to why self-determination continues to be relevant throughout the world _ from the relationship of the family as a basic social unit to the relations between nations. The question of self-determination exists in the arenas of ethnicity, identity politics and multiculturalism, in citizenship rights and in the rights of minorities. It is a problematic concept in the politics of representation that asks: who decides and for whom?

The idea that each individual, be an adolescent, adult or the child, must be given the greatest respect in terms of the freedom of choice and wellbeing is central to Sri Aurobindo’s thinking, as evidenced in War and Self-Determination. While order and unity are important, he explains, it is equally important, to allow the free play of diversity. This is a refrain that is found in most of his writings on the subject. As Sri Aurobindo observes:

“The principle of self-determination really means that within every living human creature, man, woman and child, and equally within every distinct human collectivity, growing or grown, half-developed or adult there is a self, a being, which has the right to grow in its own way, to find itself, to make its life a full and a satisfied instrument and image of its being. This is the first principle which must contain and overtop all others; the rest is a question of conditions, means, expedients, accommodations, opportunities, capacities, limitations, none of which must be allowed to abrogate the sovereignty of the first essential principle.”

The need to see the completeness of one with the completeness of all _ these remain deeply spiritual ideals before mankind. Such an ideal goes beyond the world of binaries and polarities typical of the rationality of the Enlightenment modernity; it calls for a faculty and instrumentality hitherto unknown in our individual and collective life, which is very much the need of the hour.

Free groupings

As Sri Aurobindo declares:

“But uniformity is not the law of life. Life exists by diversity; it insists that every group, every being shall be, even while one with all the rest in its universality, yet by some principle or ordered detail of variation unique. The over-centralisation which is the condition of a working uniformity is not the healthy method of life. Order is indeed the law of life, but not an artificial regulation. The sound order is that which comes from within as the result of a nature that has discovered itself and found its own law and the law of its relations with others. Therefore, the truest order is that which is founded on the greatest possible liberty; for liberty is at once the condition of vigorous variation and the condition of self-fi nding. Nature secures variation by division into groups and insists on liberty by the force of individuality in the members of the group. Therefore, the unity of the human race to be entirely sound and in consonance with the deepest laws of life must be founded on free groupings, and the groupings against must be the natural association of free individuals. This is an ideal which it is certainly impossible to realise under present conditions or perhaps in any near future of the human race; but it is an ideal which ought to be kept in view, for the more we can approximate to it, the more we can be sure of being on the right road.”

Need for multiple allegiances

Such a view of the individual and group life would entail allegiance to multiple loyalties: to the individual, the family, the commune, the province, the nation and the world in a non-hierarchical manner; that is to say, not one at the cost of the other. To realise the truth of the one, one would argue, one needs to simultaneously see the truth of the others. It must seek to realise the greatest good of the largest number of the people, especially the deprived and the dispossessed.

This view of self-determination must accept cultures and life values of individuals, groups and communities without force or duress of any kind. Most of all, it must not look at the market or the state as the arbiter of individual or social behaviour.

‘Conversation of respect’

The idea of self-determination as outlined here, relies on democratic pluralism. The main problem of democratic pluralism, as Patrick J. Hill suggests, “is less that of taking diversity seriously than that of grounding any sort of commonality. It is the problem of encouraging citizens to sustain conversation of respect with diverse others for the sake of their making public policy together, for forging over and over again a sense of shared future.”

It is through such conversations, based on acceptance, pluralism and diversity, founded on deeper psychological and spiritual principles that a greater and stronger bonding among the people and nations of the world could be forged. Self- determination would thereby find its chosen destiny and fulfilment.