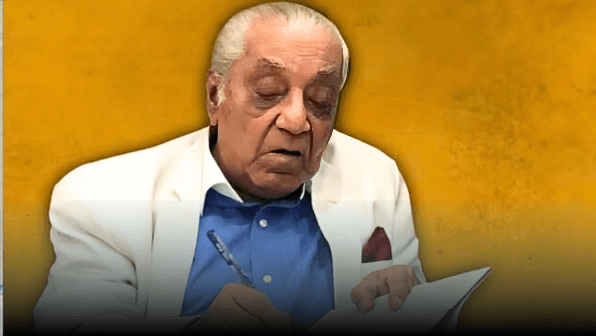

Writer and social activist Teesta Setalvad recounts her long bonding, based on shared convictions, societal commitment and activism, with scholar and political analyst AG Noorani, who she terms as the man who knew really well where and what to recall, what and how to dig and unearth and how to get it published.

Ten years and three months ago, Abdul Ghafoor Noorani, the near always frowning nonagenarian who passed away yesterday, on August 29, 18 days before he completed an enviable 94, wrote these words: “In this heartbreaking task I remain hopeful nonetheless that secular forces will reassert themselves.” AG Noorani, June 1, 2014.

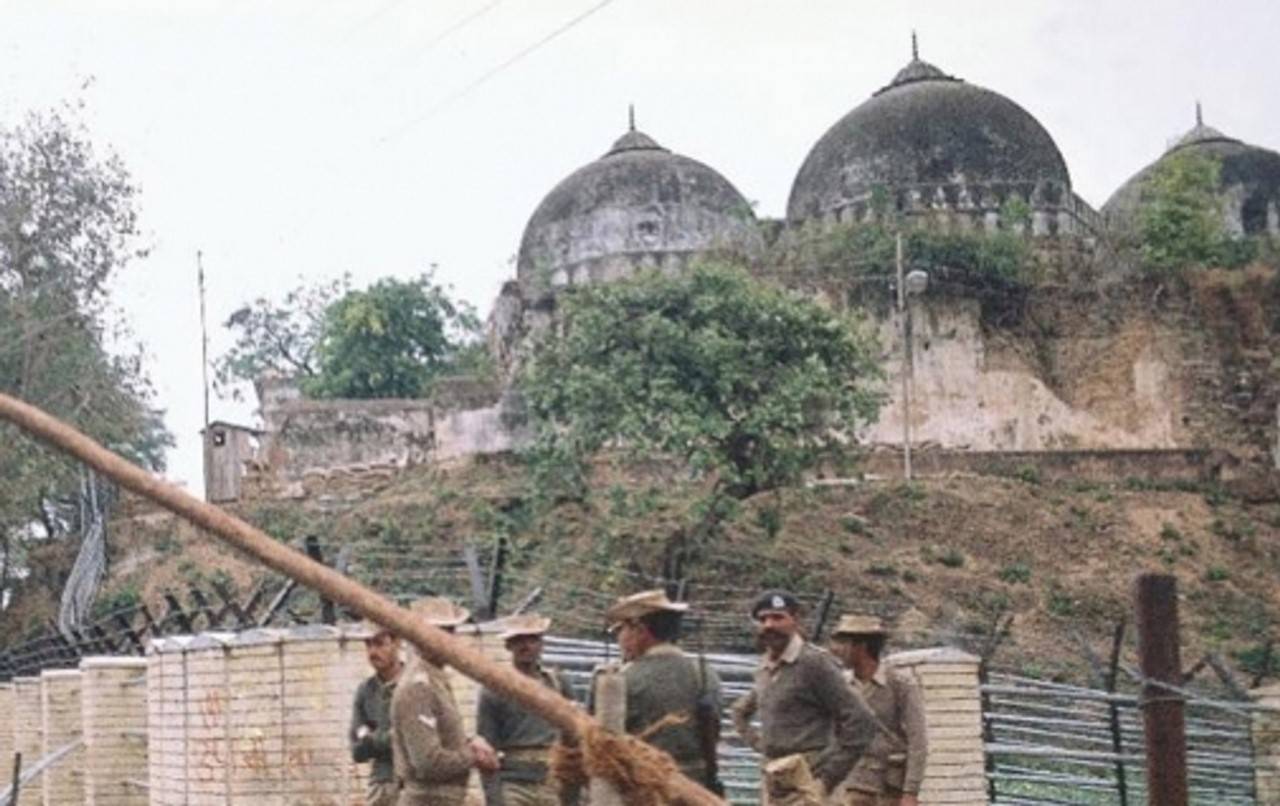

This was the last line of his introduction to the third volume, Destruction of the Babri Masjid, A National Dishonour, published by Tulika as a tragic sequel to the two-volume, The Babri Masjid-1528-2004 ‘A question of national honour’. Failing in health as he was furiously putting together his work on the shocking November 2019 Babri Masjid Supreme Court Judgement, I cannot help but wonder what he felt or was feeling post June 4, 2024 when the 18th Lok Sabha polls threw up a more empowered opposition.

The decade of the 1990s was decisive in its assault on the Indian republic and democracy. Schisms visible at multiple levels then have widened and deepened to allow for the near complete overturning of the Indian Democratic effort, whose corollary as Ghafoor saheb always said, is Secularism.

It is the decades of the early 1990s that led up to the demolition (on December 6, 1992) and was preceded by the insidious corrosion of democratic institutions and the political class that my association with AG Noorani began and grew. The near regular sight of him dressed in his inimitable coat and tie, sipping a cuppa in the Bar Council Library on the top floors of the Bombay High Court soon changed into brief, then longer meetings which thereafter took place, sometimes, at his Napean Sea Road residence.

For those of us, journalists and students of social sciences and the law, who had lived through the Bhiwandi-Bombay violence of 1984 (and reported on it), witnessed with horror India’s largest political party preside over the massacre of Sikhs in New Delhi and other cities the same year, observed at close quarters the communal conflagrations in neighbouring Gujarat in 1985, then devoured news and analyses on earlier bouts of such violence like Moradabad (1980), later Hashimpura-Meerur (1987), Bhagalpur (1989) there was, increasingly, a pattern to be seen, observed and dissected. The story of “Who cast the first stone?” that needed to be told, and re-told.

Conversations with AG Noorani were a learning in grasping the play of communal politics, seeking answers to questions that many do not ask and few answer. His minute understanding of the communal violence in Bhiwandi that resulted in the epochal Madon Commission report (1970) was eye-opening. It was this decade and his unique exploration of the violent and systemic erosions of India’s secular foundations that have found him a place in India’s gallery of legal scholars.

A lawyer by training and profession, Noorani had that reporter’s uncanny eye for thorough and complete documentation and detail. His home in south Mumbai, crammed with books and carefully filed newspaper clippings. Conversations were never short and he was a stickler for punctuality. Lucky were you if he pointed up to a shelf during such a pow wow pointed to a particular spot, identified the volume he was speaking of and shared it with you, to read!!!

More comfortable with books and newspaper clippings collected over decades, he had a few chosen friends, several admiring professional associates and publishers. A lover of choicest dishes and food, he was also a writer who eschewed modernity and gizmos. He wrote every manuscript by hand, sending all he penned to one particular typist near the Bombay High Court who not only deciphered his hand but re-typed any corrections with a second, often final draft.

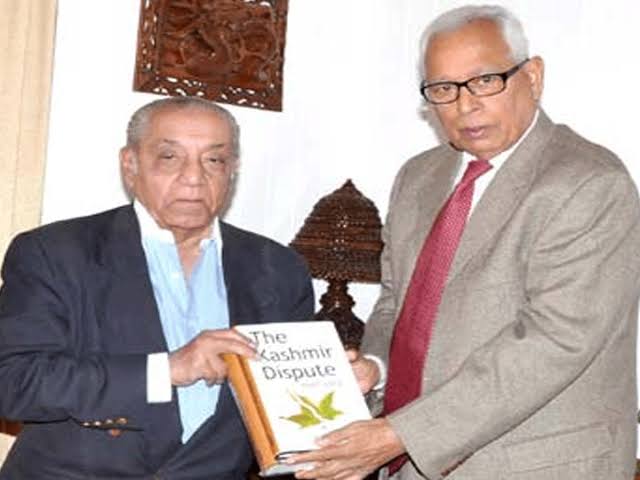

It is no wonder –given his sharp analyses of the excursions and failings of the Indian state in Jammu and Kashmir (Article 370: A Constitutional History of Jammu and Kashmir-2011)and even Hyderabad (The Destruction of Hyderabad-2014)—that, his fine, regular, writings were only published in the in Frontline and Dawn, both fine publications. Each and all of his columns including those on how a Supreme Court judgement brought sedition through the backdoor (Kedar Nath Singh judgement, 1962) are lessons for the legal writer and journalist. He was also scathing of India’s highest court when he wrote, “CJ Ranjan Gogoi drove a coach and four through the writ of habeas corpus.” For the constitutional courts –given their sensitivity to the all-pervasive (often manipulated) “social media” reading AG on jurisprudence could often be a much needed course correction.

Where and what to recall and remember, what and how to dig and unearth, and finally, how and where to get published! Meticulous detail, integrity of purpose and persistence thy name was Ghaoor saheb. Noorani’s entire body of work, that is a tribute to both a legal and journalistic hawk’s eye shine most of all because of their unalloyed moral core. He spoke not only for what is right, fearlessly but was unafraid of the ostracisms and enemies that came of this task. The story of his publishers –articles and books –is itself a chronicle of the times that remains untold.

Savarkar and Hindutva (2002)

The Babri Masjid Question 1528–2003: ‘A Matter of National Honour’, in two volumes (2003)

Constitutional Questions and Citizens’ Rights (2006)

The RSS and the BJP: A Division of Labour (2008)

Jinnah and Tilak: Comrades in the Freedom Struggle (2010)

Article 370: A Constitutional History of Jammu and Kashmir (2011)

Islam, South Asia and the Cold War (2012)

The Destruction of Hyderabad (2014)

Each and all of these books—and these are only some of them– are meticulous attempts at historicising India’s contemporary reality and exposing the proto-fascist majoritarian forces out to capture and seize democracy. They are a must read for contemporaries, students, lawyers and journalists, all Indians concerned and involved in the present. They are also invaluable documentation for the future.

Among all, I found myself browsing – yesterday and this morning, as I absorbed the news of his demise – the three huge volumes on the Babri Masjid demolition. They contain all and everything there is to know of this shameful act from the duplicity of the main players to the fickleness of Indian state functionaries. Two of the three are dedicated to the memory of C Rajagopalachari, “a devout Hindu, a great Indian and a consistent champion of minority rights” but it is this despairing plaint in the final one, quoting Maulana Hazrat Mohani that is the most heart wrenching, They are the murderers too, they are the prosecutors too, Whom then will my kin prosecute for my murder? (Wahin kaatil, wahin mukhbir, wahin munsif therey Aqrba merey Karen khoon ka dawa kis par?)

That Noorani should choose Mohani to quote from, in 2014, is telling. A noted poet of the Urdu language, it was Mohani who coined the slogan that reverberates in every Indian street protest, “Inquilab Zindabad”, Long Live the Revolution. In 1921, Mohani along with Swami Kumaranand are believed to be among the first persons to have demanded complete independence through a motion moved at the Ahmedabad session of the Congress.

This was the legacy that AG Noorani’s writing and vast body of work upheld. Maybe, just maybe, in August of 2024, post-election results, he would have died a more hopeful, less despairing man. Now, both India and its political opposition need to reaffirm absolutely what AG Noorani lived and died for.