The Adani affair: Collapse of Regulatory Structures

The AIDEM’s Cover Story on the ‘Big Crash’ of the Adani group of companies and its larger economic and political fallout highlights an important statement from the People’s Commission on Public Sector and Public Services, a public interest group consisting of eminent academics, jurists, erstwhile administrators, trade unionists and social activists.

The Hindenburg revelations, which triggered a period of unprecedented volatility in Indian capital markets, pertain to the recent meteoric rise of one of India’s top conglomerates, the Adani Group. At the heart of the issue is how a permissive regulatory regime facilitated this rise.

The full-blown controversy surrounding the Adani Group has brought to the fore a number of deeply worrying facets of the regulatory regime governing India’s capital markets. The crux of the allegations made by Hindenburg Research, which precipitated the unprecedented turmoil in the stock markets, pertain to the ownership structure of the companies in the Adani Group. In particular, the allegation that a web of shell companies located in tax havens are connected to key personnel of the Group own shares of the companies implies that the extent of “public” ownership of shares of these Group companies is exaggerated and is in violation of the regulations set by the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI), which is the prime regulator of Indian capital markets.

SEBI regulations stipulate that at least 25 per cent of the shares of a listed company be with the “public”, that is, persons or entities not connected or controlled by the promoters of companies. This stipulation is meant to ensure that there is wider dispersal of ownership, which would allow for better price discovery of the true value of the shares of a company, and therefore, of a company’s true worth as determined by the market.

The Hindenburg allegations about the use of shell companies are critical because such structures facilitate easier manipulation of the Adani Group companies’ share prices, which in turn would make it possible to not just inflate their valuation, but leverage higher valuation to mobilise greater quantities of debt than would have been possible without the use of such opaque ownership vehicles.

SEBI’s statement asserting that Indian capital markets are “stable” and that they are “function(ing) in a transparent and fair manner” conceals the real issues at stake. First, Hindenburg’s allegations have nothing to do with the stability or otherwise of the Indian stock markets. Instead, its allegations suggest a dereliction of regulatory duties by SEBI, in ensuring that all market participants comply with its regulations. Indeed, if anything, the stability of markets rests on such compliance.

The February 9 decision of the MSCI (formerly Morgan Stanley Capital International), an investment research firm that also constructs market indices, that several constituents of the Adani Group can no longer be eligible for its indices is damning indictment that SEBI has been in gross dereliction of its key duties as a regulator. The MSCI, which had undertaken a review of its indices in which Adani Group company shares were constituents, said immediately after the Hindenburg revelations. “MSCI has determined that the characteristics of certain investors have sufficient uncertainty that they should no longer be designated as free float pursuant to our methodology.” It is significant that the shares of the Adani Group companies, which had recovered after a spectacular collapse, fell sharply after the MSCI statement on February 9.

Commenting on the developments, Hindenburg founder Nathan Anderson remarked on Twitter: “We view this as validation of our findings.” SEBI’s conduct is in sharp contrast to that of MSCI; while the private market research firm thought it fit to immediately address the issues that had a bearing on the credibility and integrity of its own indices, the national watchdog has been revealed as a hapless spectator, or, at worst, one that is indulgent to the point of obliging the whims of a buccaneering corporate czar.

Secondly, it appears that SEBI’s own “investigations” into the use of shell companies has been going on for almost two years without any tangible progress. This is indeed serious because it reflects at best either lethargy, carelessness and dereliction of its basic regulatory duties, or, at worst, a permissive regulatory regime that encourages cronyism.

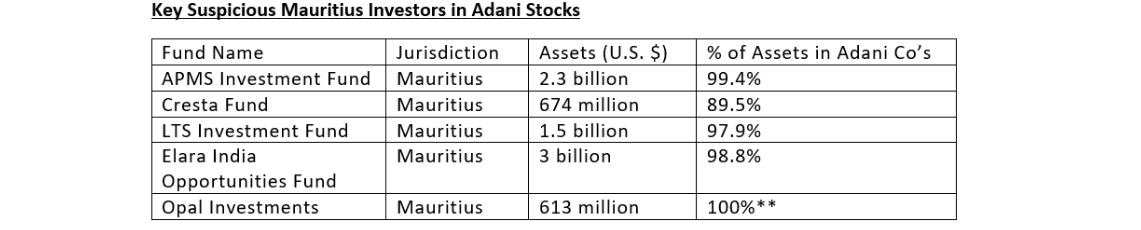

In this context, it is pertinent to recall the issues raised by Mahua Moitra in Parliament on July 19, 2021. In particular, she asked a question about the Adani Group’s beneficial interests in Foreign Portfolio Investors (FPIs) who invested in six listed Adani Group companies. In particular, she wanted to know whether the regulators had initiated any investigation. In reply, the Minister of State for Finance confirmed that while the SEBI and the Directorate of Revenue Intelligence had undertaken investigations against a few FPIs, no investigation had yet been undertaken by the Enforcement Directorate. Citing confidentiality, he refused to disclose whether the Income Tax Department had conducted any investigation. Further, he provided a long list of beneficial owners of FPIs who had invested in the six Adani companies as on June 30, 2021. Among them were many Mauritius-based FPIs.

Seen in this context, these issues raise serious questions of SEBI’s role as a regulator to ensure that its rules are complied with. Why has SEBI taken so long to determine the status of the shell companies and their linkages with the listed companies of the Adani Group. And, what has it done about the grave violations of its listing rules if these allegations are indeed true?

Thirdly, and disturbingly, recent media reports reveal that the authorities in Mauritius have been in touch with SEBI, indicting that SEBI may well know or may have already been in the know about the true identities of “beneficial owners” in entities that own shares of the Adani companies. (“SEBI can access all Mauritius information: Mahen Kumar Seeruttan” – Mint, February 7, 2023)

The Mauritius Minister for Financial Services and Good Governance is reported to have reiterated that Indian regulatory agencies “are allowed full information, even up to the ultimate beneficiaries.” While insisting that such information has been shared with the Indian agencies on an ongoing basis “for quite some time”, he revealed that such information included information pertaining to the Adani Group companies. These revelations indicate that SEBI’s fruitless and prolonged “investigation” into the true extent of “public” shareholding in the Adani Group companies has facilitated the continued abuse of Indian capital markets by sharp operators.

While SEBI’s failure to prevent the use of shell companies has become obvious, even more shocking has been the role of key Ministries in the Union Government, particularly those in charge of Finance and Corporate Affairs. It is shocking that neither Ministry has thought it fit to even define a shell company, let alone prevent the use of such opaque structures, which are detrimental to the growth of a healthy capital market that is transparent to all stakeholders. Answering a Rajya Sabha question on shell companies on February 6, 2018, the Corporate Affairs Minister stated “The Companies Act, 2013 does not define the term Shell Company. However, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) defines a Shell Company as a company which is formally registered or otherwise legally organised in an economy but which does not conduct any operation in that economy other than in a pass through capacity.”

To make matter worse, the Government’s decision of August 2022, to allow Indian corporate entities to invest in foreign locations, provides ample scope for Indian entities to use shell companies located in tax havens to indulge in round tripping, a mechanism that enables rerouting of black money into the Indian economy. The decision also permitted domestic entities to make overseas investments, even if they were under investigation by any investigative agency or regulatory authority, a provision that opened the overseas doors for tainted individuals and companies to continue with round tripping. This raises concerns about the motives underlying the decision.

The Reserve Bank of India’s (RBI) recent action in summoning details of loans given by Indian banks to the entities of the Adani Group is shocking, to say the least. One would assume that RBI, as the key regulator of the Indian banking system, would have had this information with it on a real-time basis. Its recent assurance that there is no danger to the banking system because of excessive leverage does not inspire confidence, purely because one wonders whether all the relevant information has been factored in.

In fact, about five months ago, when CreditSights, a research wing of the U.S.-based Fitch rating agency, cautioned Indian regulators about over-leveraged operations of the Adani Group, the People’s Commission had written to the RBI Governor demanding that the banking sector regulator assess the implications of this for the health of the financial institutions and for the stability of the financial system. It is obvious that RBI failed to act on our letter.

The Adani fiasco highlights the futility of the government’s reliance on private global champions to power the Indian economy. Moreover, such a misplaced reliance necessarily rests on a culture of “cronyism”, while holding back the potential of publicly-owned Central Public Sector Enterprises (CPSE). This mindset is is reflected in the Government’s commitment to disinvestment in CPSEs as well as its “asset monetisation” programme, which is only a euphemism for the handing over valuable national assets at throwaway prices to private entities.

The volatility in the stock market is the more serious problem is the abject dereliction of duties by multiple actors in the Indian regulatory landscape. At the very top of the governance structure are key Ministries and Departments in the Government, which have failed to establish checks and balances; SEBI as the market regulator has failed to implement its own rules, which bring into question the credibility and integrity of the Indian capital markets; and, the banking sector regulator has been a mere bystander, allowing a bubble to assume threatening proportions. In sum, the Adani affair highlights the wanton neglect of national regulatory systems, mechanisms and structures and signals that India is open for abuse at will by sharp operators.

In the light of these worrisome developments, the People’s Commission urges Parliament and the people at large to pressurise the Government to:

Urgently promulgate laws and regulations that ensure that shell companies established in overseas jurisdictions are in compliance of national laws and regulations. This would make it amply clear to foreign entities that there is zero tolerance of violations of Indian regulations.

Ensure the autonomy of regulatory agencies such as SEBI, RBI, Registrar of Companies, so that they function with a degree of transparency.

Functional autonomy for investigation agencies such as the Central Bureau of Investigation, Enforcement Directorate, Directorate of Revenue Intelligence, Income Tax Department, Serious Frauds Investigation Office, etc. The arbitrary and selective conduct of their investigations in recent times is obvious to all. Their control by the executive is what enables not just their use as tools of harassment but also as a means of serving the needs and demands of cronies. This needs to change.

Stop forthwith the disinvestment and asset monetisation drives as they are detrimental to national interest.

In conclusion, we wish to point out that there is widespread apprehension that many corporate entities appear to be operating through a multi-layered and complex web of shell companies set up in tax haven jurisdictions. This has the effect of creating a shadow economy, which enables them to not only evade taxes in India, but to manipulate markets, pass on funds to political parties through opaque vehicles such as Electoral Bonds, and mock at regulatory norms. The power to influence the political executive to adopt policies and laws that promote their own interests, and to the overall detriment of the public interest, is simply unacceptable to a functioning democracy. The perpetuation of such structures undermines the nation and its cherished institutions.

To read and view more from the Adani Crash Cover Story package, Click here.