Rajasthan’s Right to Health Act: The Way Forward and Some Hitches

By enacting the Right to Health Act, 2022, the Rajasthan Assembly has written a remarkable chapter in the history of health legislation in India. This is undoubtedly the first Act that explicitly brings health (care) into the ambit of citizens’ rights and fixes the responsibility of delivering it on the state. The Rajasthan government has stated that it is planning to improve upon this legislation as well. This gives hope as Rajasthan is also the pioneering north Indian state to roll out the much discussed free medicines scheme almost a decade ago. The scheme aimed at providing prescribed medicines free of cost to all patients in the State, thus considerably reducing out-of-pocket spending by the common people on health care needs.

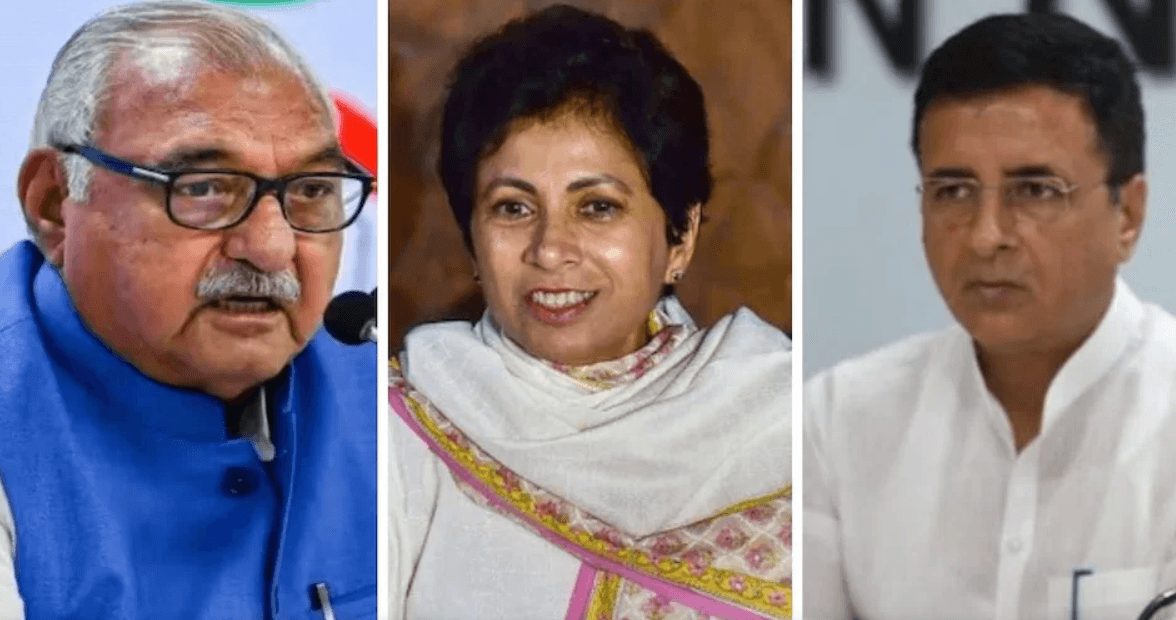

Rajasthan CM Ashok Gehlot

Rajasthan CM Ashok Gehlot

As someone who has engaged actively with public health in different capacities _ as a community practitioner, as a social activist, as a public health/health systems/health policy researcher, as an academic, and a former administrator _ I have analysed this legislation. Here, I am sharing my reflections, with a hope that these will help the State of Rajasthan to strengthen its initiative and the other States to enact a comprehensive public health law:

- While the law is titled the Right to Health Act, it’s on the right to health care services, especially the emergency services. In this area, a lot more features have to be added to make the Act comprehensive. Significant additions in terms of entitlements related to preventive and promotive health, environmental health, social health, health determinants, and so on, have to be made. However, we need to note that often health, public health and health care are considered one and the same by many quarters.

- Even to fulfil the current minimal level of commitments made by the Act, the state has to put in a lot of efforts to make the government-run health service delivery network more reliable, responsive, and accountable. This means filling the human and other infrastructure gaps on a priority basis, addressing behavioral gaps, updating technologies regularly and substantially improving the quality of care. All these measures require not only sufficient financial resources but also institutional abilities and capacities to utilise these resources in the best possible manner. Above all, leadership and political will are absolutely essential because the right to health cannot be achieved in a five-year tenure of any State government. We need to also note that this law has been enacted during the last year of the incumbent government, which makes the leadership and sustainability requirements even more crucial.

- For including private health providers in the health care network in an equitable manner, the state will have to do away with the insurance coverage-based systems, which have been proved to be not useful for the needy populations and wasteful for the exchequer. Instead, a just and justifiable rate-fixation system for services as well as a dignified and time-bound payment system need to be set up under a state- managed risk-pooling mechanism, which will save a lot of financial resources for the state. For managing reimbursement of out-of-pocket expenses by the individuals, the state can rely upon a localised system run by reliable community level institutions. Such systems should be supported by well-equipped regulatory systems to ensure the quality of facilities, processes, actual service delivery and payments therein.

- Grievance redress systems should be set up in an inclusive manner avoiding conflicts of interests _ which is a problem with the present Act _ so that these systems could be extended to both government and privately provided services. In addition to this, community level feedback and improvement systems are also a must for realising the right to health in a participatory manner.

- To ensure that the most vulnerable sections of society avail themselves of the various benefits and services provided under the Act, it has to be made more inclusive and equitable in terms of instrumenting systems.

- A strong information system is essential for people and providers to understand the Act’s provisions and to positively improve the health seeking behaviour and quality of service.

Taking the critics along

At times, vehement opposition to something shows its significance. This is the case with the present Act. The State government successfully managed to negotiate with those who opposed the Act and notify it in the gazette. At the same time, I feel that the government should have been a bit more careful in drafting the contents and processes of the Act, which would have averted the protests. Among the critics of the Act were well-meaning medical professionals, who seem to be genuinely concerned about some of its provisions. Of course, nothing can be done about those with conflict of interest who will continue to disseminate misinformation and provoke agitations despite the best intent and contents of the Act.

Nevertheless, it is also to be stated that the state did set up a consultative system in the run-up to the enactment of the law, and has accepted a number of demands of the agitating; in fact, such concessions have weakened or compromised many important provisions of the Act. I can only hope that the government will be able to strengthen such weaker provisions on the go, and the agitating professional communities will soon realise this fact, come forward and help the government strengthen and roll out the Act in a better way.

Doctor’s protest against Rajasthan Health Act

While it is important to bring clarity to various provisions and ensure justice to the private service providers’ demands, it is also the duty of medical professionals and associations to respect and strengthen the law’s primary intent of delivering people’s health rights. I am also hopeful that the Government of Rajasthan will formulate affirmative rules that will facilitate a meaningful rollout of the Act and introduce changes to make it a comprehensive legal instrument. The government must take the active support of those who have been working for people’s health in strengthening the provisions of the Act and making it comprehensive. Organisations like the Jan Swasthya Abhiyan has already come forward to offer such support.

The Assam experience

There are some important failures to remember too. In 2010, the State governmentof Assam had enacted The Assam Public Health Act, which sought to establish people’s health rights in India for the first time. This Act defined the health and health care rights of the people, duties and rights of the providers, and the health services to be rendered to the people across the State – although the title of the Act did not explicitly express the “rights” paradigm like the Rajasthan did. Unfortunately, the last 13 years have not seen any major progress in the implementation of this Act.

Rajasthan has the opportunity and momentum that Assam has lost. The Rajasthan government, medical and health professionals in the State, media personnel and the people of Rajasthan (and also other States) have a lot to learn from the history of the Assam Act. Worryingly, the current Rajasthan government is at the end of its five-year tenure, a situation similar to Assam where the Health Act was enacted by the Congress when the Assembly elections were round the corner. Though the Congress returned to power, the momentum created by the passing of the Public Health Act was not followed up by the succeeding government because the Health Minister of Assam who had tabled this Bill in the Assembly defected to another party and became the Chief Minister of the State. As a result, the Act lies in cold storage.

Assam CM Himanta Biswa Sarma, who tabled the Assam Public Health Act in Assam assembly when he was a minister in the Congress government in 2010

I sincerely believe this will not be the case in Rajasthan. It should not be too because the right to health is definitely a political tool to achieve the goal of ‘health for all’ and empower those committed to people’s health. However, the promise of health care should not be reduced to a tactical election promise to win votes. This is where I expect the Rajasthan government, whichever party leads it, to carry forward the ‘health for all’ agenda taking along all sections of people in a sincere and serious manner.

I am also thinking of how the other States can establish the right to health and health care in their respective jurisdictions, learning from the Rajasthan case. A lot of groundwork and system strengthenin needs to be done by States intending to make such initiatives comprehensive and acceptable. While the duties and accountability of the private sector needs to be clearly stated and institutional measures to realise these to be built in an adequate manner, the state should cover the justifiable costs incurred by the private sector. One has to realise the importance of taking the private actors on board and to ensure timely and smooth transfer of financial resources to them.

Kerala and Tamil Nadu

The States of Kerala and Tamil Nadu demonstrate how health entitlements could be ensured. The Public Health Act enacted by the Kerala Legislative Assembly recently and the preparatory measures being undertaken by the Tamil Nadu government to establishing the right to health show that they are legally sound ground. The way the health systems, private actors and the communities worked together in these States during the Covid-19 pandemic recently, led by the local and State governments indicate there preparedness to move forward on the right to health front. This does not mean that the other States cannot do this. Let us hope that the journey that Rajasthan has embarked on will show the way to the other States in establishing health as a legally enforceable right.