Mrinalda’s Camera: Three Distinct Gazes (Part 01)

Mrinal Sen is a luminary in the Indian film world. His unparalleled legacy calls for a commemoration on the occasion of his birth centenary this year. His aspiration was to imbue uniqueness and inventiveness into each cinematic rendition. This three part series is an attempt to reread three of his celebrated films, each approaching the art of filmmaking in distinct and remarkable ways. The films are Bhuvan Shome (1969), Akaler Sandhane (1980) and, Ek Din Achanak (1989). He was a director who constantly experimented and took up every film as a challenge.

Mrinalda, a proponent of artistic autonomy, navigated diverse routes within parallel cinema. His films unapologetically spoke many tongues. Inspired by Marxism and its artistic perspectives, he ceaselessly sought innovation throughout his cinematic journey.

Bhuvan Shome

Bhuvan Shome, was the film that marked his entry, as a film maker who held great promise. It presented a fresh and captivating experience for the audience, heralding the onset of a new cinematic wave in India. The storyline primarily focused on the encounter between Bhuvan Shome, a stern railway official, and a village girl. It swiftly garnered interpretation as a narrative of a village girl exerting influence on a bureaucrat. Satyajit Ray wrote that it was a case of a bureaucrat refined by a village beauty. Mrinal Sen contested this perspective. In line with his political ideology, he opposed the notion of reforming or compromising with the bureaucracy. According to Mrinalda, the very idea of attempting to reform was reactionary. He mentioned that in his film, the proximity with Gauri allowed Bhuvan Shome, to recognize the tragedy unfolding within his own being.

The film begins by presenting Bengal, showcasing images of renowned Bengalis such as Vivekananda, Satyajit Ray, Tagore symbolizing Suvarna Bengal appear on screen and then scenes portraying street demonstrations, protests, and riots emphasizing Bengal’s distinctiveness. Mrinal Sen then introduces Bhuvan Shome, a quintessential Bengali characterized by honesty, punctuality, discipline, and an unblemished ethical stance. Bhuvan Shome’s commitment to his work is unwavering, and he maintains a principled and uncorrupted demeanour. Despite being a diligent and upright figure, Bhuvan Shome grapples with loneliness, without a family but amidst his subordinates, who do not really respect him and are wary of his sternness. Bhuvan is portrayed not as an evil lord driven by political connections, rather as a strict and honest official. Notably, Bhuvan Shome is primarily driven by an inherent anti-corruption ethos, reflecting a deep moral sense of absolute goodness. Mrinalsen’s portrayal of Bhuvan Shome defies categorization within the political genre of a bureaucrat.

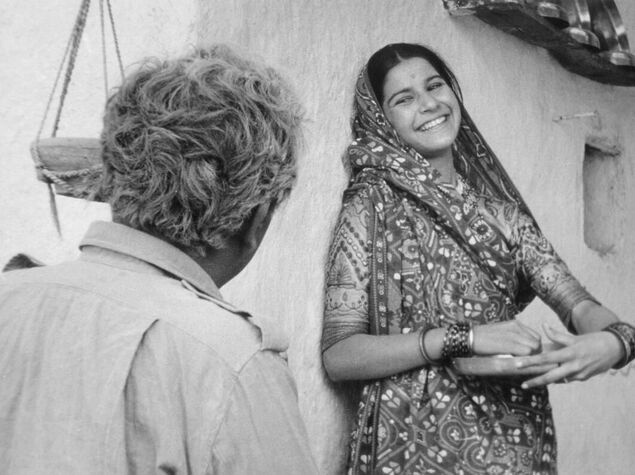

The pivotal moment occurs when Bhuvan Shome goes on a trip to the countryside hunting ducks to take his mind away from the tedious routine of official duties. This experience reveals the limitations of his structured and compulsive demeanour. After years of systematic service, the outside world unsettles him, evident in his fear of a speeding bullock cart coupled with discomfort in the leisurely transport. Subsequently, Gauri’s buffalo startles him, prompting a frantic escape, highlighting the adverse reactions his body language and speech elicit in others. These experiences during the bird hunting trip prove an opportunity for profound self-discovery and transformation.

Despite his punctuality and discipline in official matters, Bhuvan Shome realizes his ignorance in various other aspects of life. The initially fear-evoking buffalo transforms into a friendly presence in the company of Gauri. Gauri’s remarkable qualities-competence, expressive freedom, determination, resourcefulness, and courage—astound Bhuvan Shome. The village girl introduces him to a new world, characterized by spontaneity, love, cooperation, and beauty. Despite the unease in the audience regarding Gauri’s sympathy towards Bhuvan Shome’s interest in bird hunting, the film takes a surprising turn, Gauri doesn’t reinforce or support Bhuvan Shome’s inclination to hunt birds. Instead, she becomes a catalyst for a profound change in him. She guides him towards valuing and protecting the birds with love, diverting him from his earlier fascination for hunting. As Bhuvan Shome leaves Gauri, her positive influence continues to resonate within him.

The shift in interest becomes evident as he entrusts her with the captured bird, urging her to safeguard it alongside the black sparrow. Bhuvan Shome experiences distress upon discovering that Jadhav Patel, the corrupt ticket inspector he was adamant about punishing, is Gauri’s husband. This revelation challenges his earlier resolve, pointing to his evolving character. Gauri emerges as a beacon of light in Bhuvan Shome’s monotonous and messy life,teaching him about Nature and its value. At the end of the film, Bhuvan Shome’s interaction with Jadhav Patel in his office room emphasises the profound transformation that he undergoes, symbolizing a significant shift in his outlook and approach to life.

Bhuvan Shome’s gaze within the film represented a call for a futuristic rejuvenation of cinematic techniques. Drawing inspiration from Marxist filmmakers like Godard, the film incorporated extended documentary-style shots, with a more unconventional and contemporary cinematic approach. Notably, the scenes in Bhuvan Shome, involving a bullock cart bore resemblance to a documentary film, emphasizing its authentic depiction.Furthermore, the initial scenes portraying Shom’s office work at the start of the film offered a novel experience to the Indian audience. Mrinalsen’s films indeed pioneered innovative trends in Indian cinematography. His unique directorial approach introduced fresh elements to Indian film art, characterized by unusual scene transitions, use of animation, unexpected close-up shots, and covert actions, all of which added a distinctive flavor to his storytelling. This departure from conventional filmmaking showcased Mrinalsen’s progressive thinking and willingness to experiment with storytelling methods. It is worth mentioning that Mrinalda’s later films did not feature the satirist or cartoonist characters present in Bhuvan Shome; underscoring the evolution and diversification of his filmmaking style over time.

Part Two of this Series focusing on ‘Akaler Sandhane’ released in 1980 to follow. Stay Tuned.