Karnataka Elections; Bipolar or Tripolar?

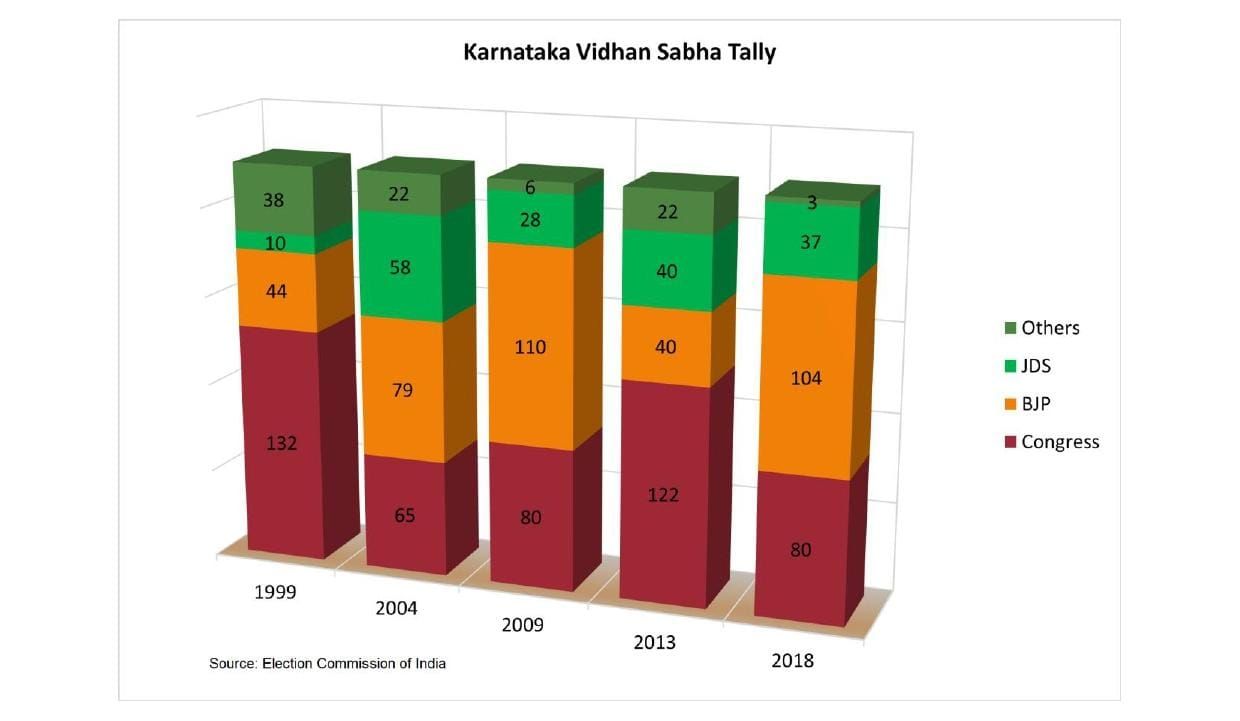

Karnataka has a history of multi-party politics, with no single party consistently dominating the political landscape. It has never re-elected ruling parties since 1989. While the Congress and the BJP have dominated the State’s electoral contests many elections in the few past years, the Janata Dal (S) has continued to be a significant third factor.

The only time a single party has won a clear majority in the last two decades was in 2013, when the Indian National Congress returned to power after a gap of nine years and Siddaramaiah became the Chief Minister.

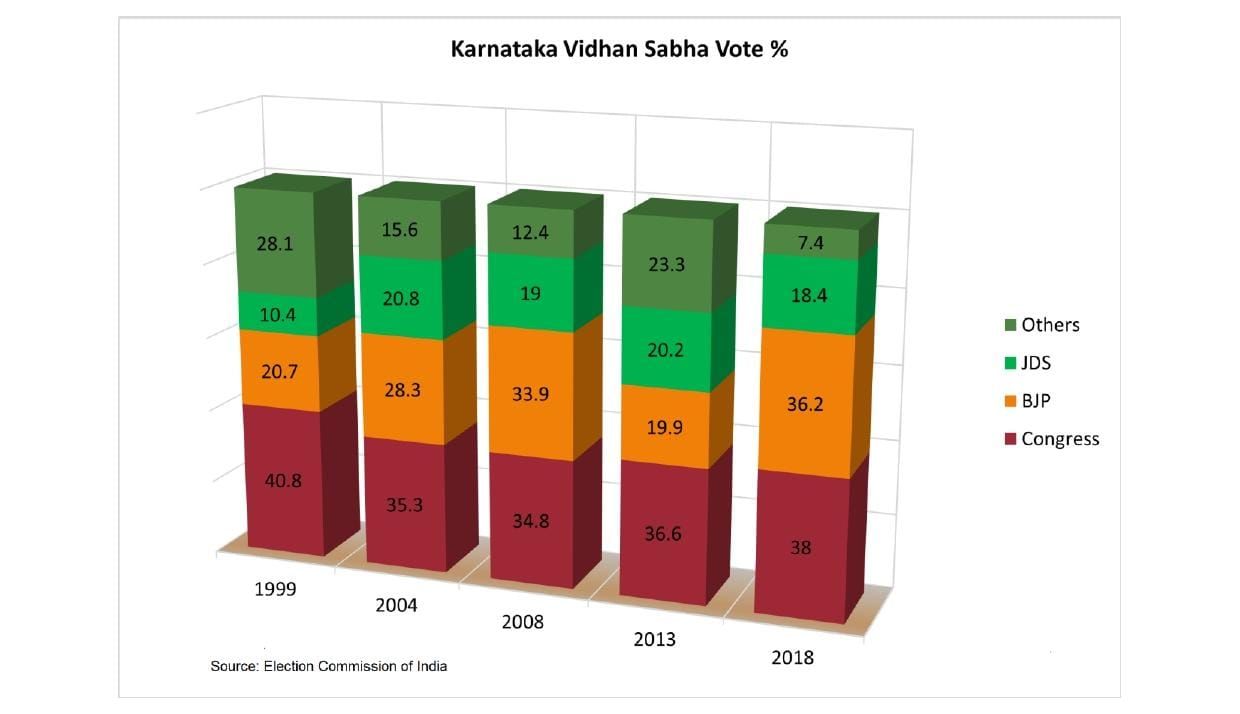

Interestingly, other parties and independents received a little more than 20% of the vote in this election. Other than the big three, two smaller parties played important roles. B. S. Yediyurappa‘s Karnataka Janata Paksha (KJP), which he formed after he resigned from the BJP in 2012, received 9.8 per cent of the polled votes. B. Sriramulu’s Badavara Shramikara Raitara Congress (BSRCP) received 2.7 per cent of the vote.

With Yediyurappa and Sriramulu rejoining the BJP in 2014, these two parties ceased to exist. The impact of these homecomings was clearly visible in the 2018 elections. Even though the BJP did not manage to secure a clear majority (its tally was 104 in the 224-seat Assembly), its vote share saw an impressive improvement, from 19.9% in the previous election to 36.2%. The vote share of the other parties makes it clear that the major reason for the BJP’s gain was the dissolution of those smaller parties. In fact, the Congress managed to secure a higher vote share than the BJP (38.06%), even though it managed to win only 80 seats in the 2018 elections.

Towards a bipolar political landscape

The political landscape of Karnataka is clearly tripolar. Three major political parties have received roughly 80% of the total votes cast since 2004. However, a vote share analysis by constituency reveals a more nuanced picture.

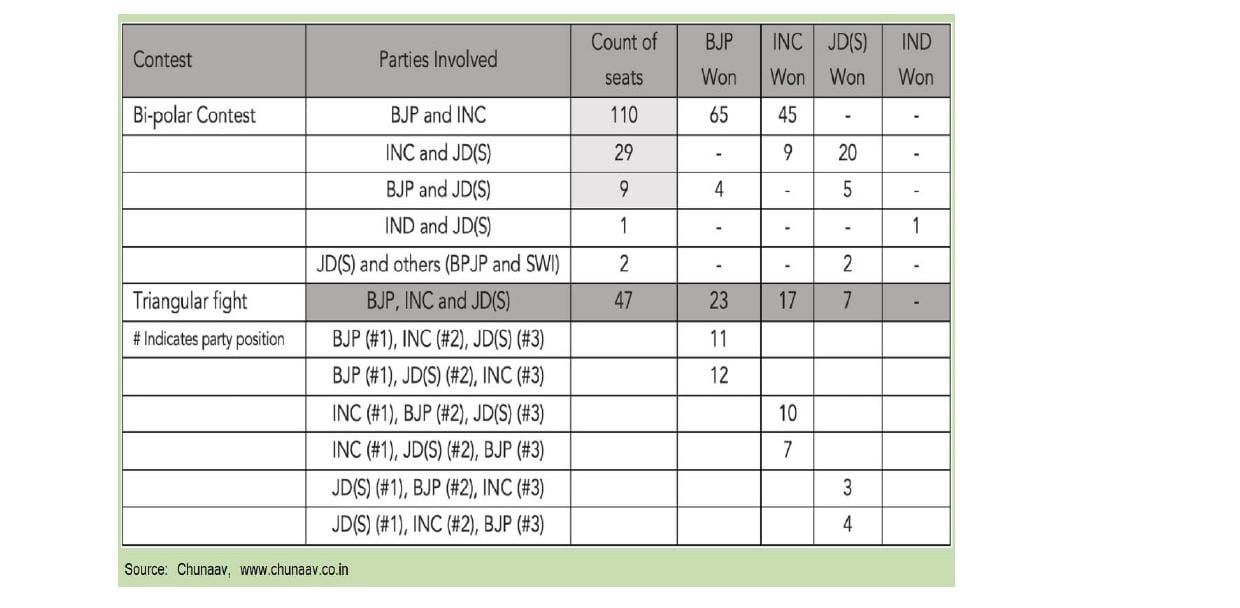

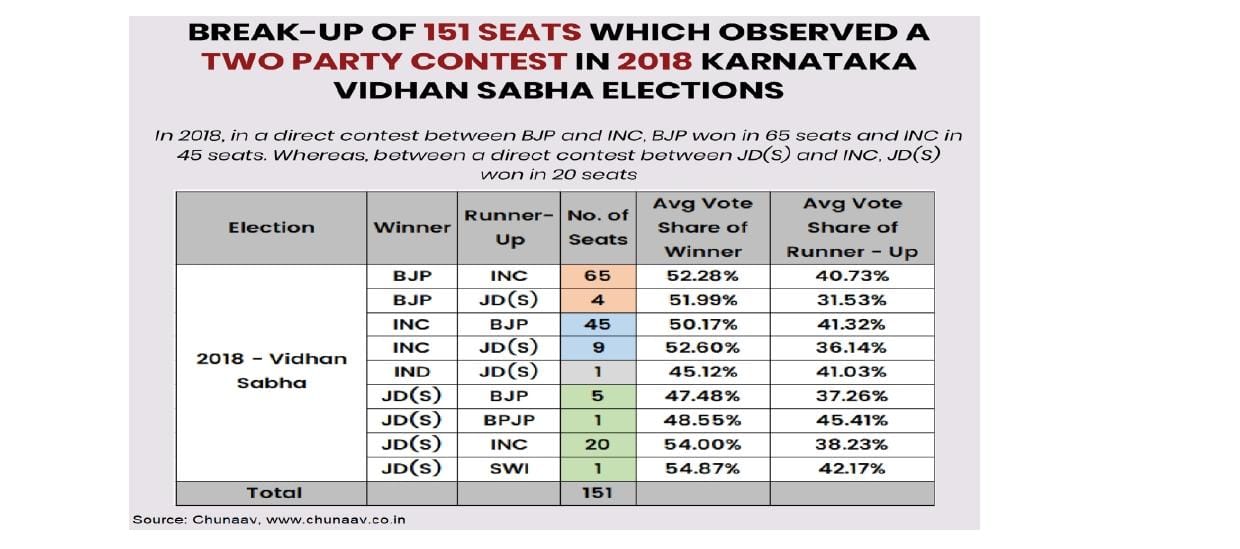

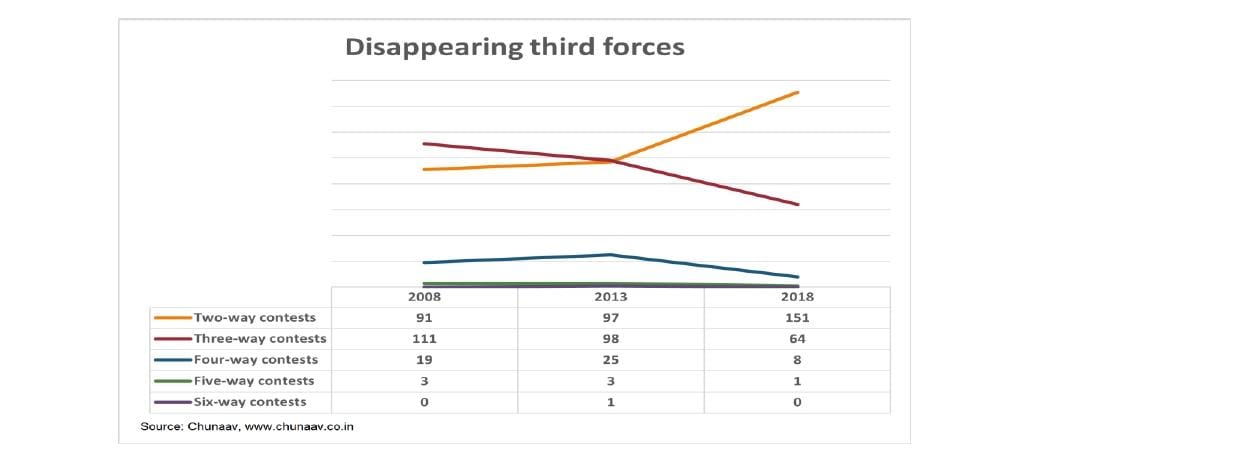

According to data compiled by Chunaav, an organisation focused on actionable political intelligence, the 2018 Assembly election saw ‘two-party contests’ in 151 of the 224 seats The winner and runner-up together received more than 80% of the votes in these seats, essentially making the contest bipolar. In other words, in roughly 70% of the constituencies, only two prominent parties competed against each other. No third political force has significantly impacted the outcome of these elections.

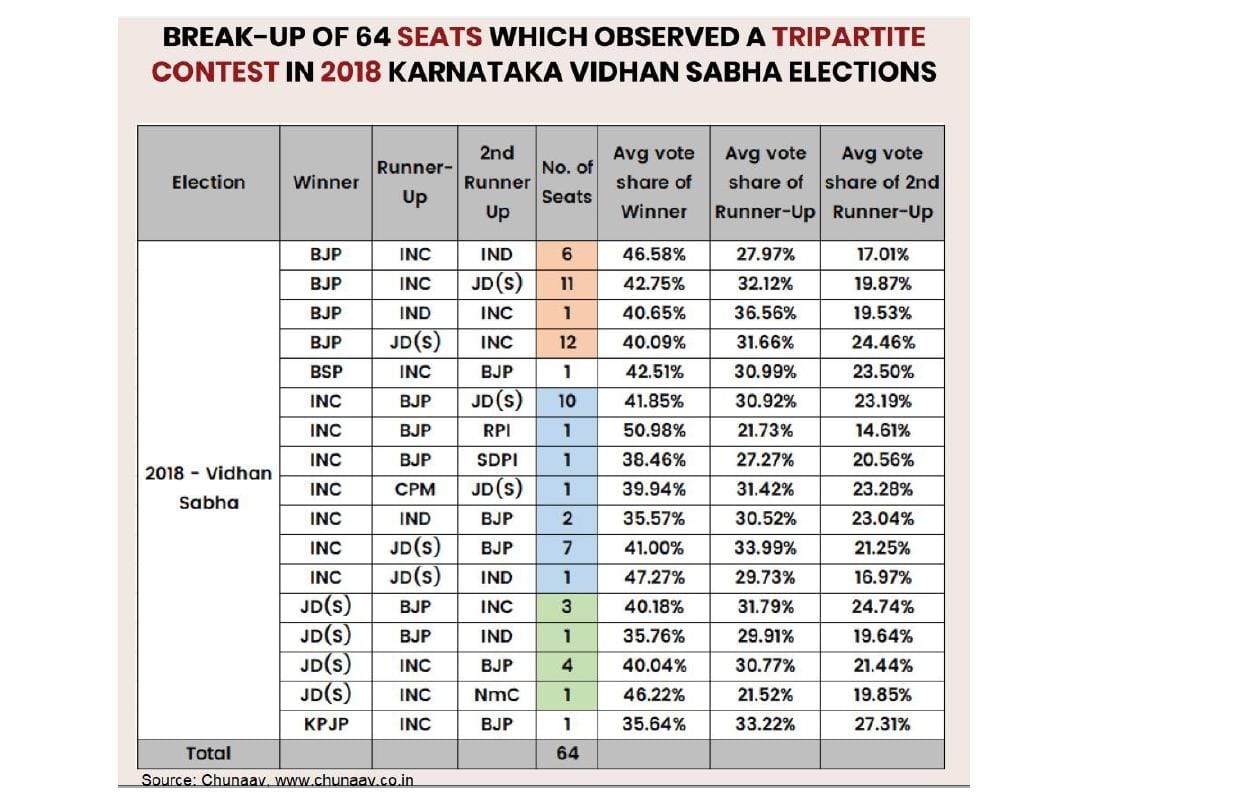

‘Three party (tripolar) contests’ happened in only 64 constituencies. Nine constituencies witnessed a minimum of three significant political formations competing.

In 110 bipolar contests, the fight was between Congress and the BJP. While Congress fought with JD(S) in 29 constituencies, the BJP had a bipolar contest with it in only 9 seats.

The BJP won 65 of the 110 seats in the direct contests between the Congress and the BJP. An interesting aspect to note in the bipolar contests is that in 95% of the cases the winner secured more than 50% of the votes.

In most tripolar cases, it is clear that the results would have been different in the absence of the three-way division of the votes.

The break-up of bipolar and tripolar contests and voting share patterns are shown in the tables below:

Disappearing third forces

Though bipolar contests became prominent in 2018, that has not been the case in the period prior to 2018. In that period, there were more tripolar contests than bipolar contests. In 2013, while there were 98 three-way and 25 four-way contests, two-way contests were only 97. In 2008, these numbers were 111, 19, and 91 respectively.

This seems to indicate that, at the constituency level, alternatives to two main contestants are losing relevance and contests are essentially becoming bipolar. It doesn’t necessarily mean that this consolidation is affecting any particular political formation specifically.

The AIDEM presents the opinion of common people about the impending elections to the Karnataka state assembly: Karnataka Janathayonthike.