Climate Home – The AIDEM Investigative EXCLUSIVE

Senior Journalist Akshay Deshmane exposes how giant Indian coal companies influenced the Narendra Modi led Indian government to weaken pollution regulations and expand the sector.

The Indian government weakened rules to curb pollution caused by its expanding coal industry after lobbying by top producers, even as it agreed internationally to phase down the use of coal, Climate Home has found.

India’s coal giants pushed back hard against environmental regulation meant to tighten up the disposal of fly ash – a byproduct of coal-fired power plants known to harm both humans and the environment if not managed properly.

Letters sent by coal companies to the Indian government, and accessed by Climate Home News through freedom of information requests to government agencies, reveal lobbying efforts to weaken federal rules between 2019 and 2023 by Coal India Limited (CIL), the world’s third-biggest coal mining company, and National Thermal Power Corporation(NTPC), one of the world’s top 10 coal-fired power companies. Top management at the state–run giants claimed that their organisations would not be able to fully comply with the regulations, which aimed to control fly ash disposal after decades of public health impacts for local communities. Even after the rules were approved, the companies continued efforts to weaken them, in some cases successfully.

The coal companies argued that financial constraints would keep them from meeting the new requirements to clean up waste accumulated over decades and prevent further ash pollution, according to the accessed documents.

In some cases, lobbying got results and regulations were eased, with the environment and power ministries drawing on arguments from both companies in official correspondence between government agencies.

In 2021, while the proposed fly ash mandates were under discussion within India, the country was negotiating the COP26 climate pact in Glasgow, which calls on governments to take action “towards the phase-down of unabated coal power”.

At those UN talks, India was widely reported to have rejected stronger language on a global shift away from coal, but it agreed to scale back unabated coal power, produced without technology to reduce its climate-heating emissions.

Despite this deal, coal infrastructure around the world has since grown, mostly driven by added coal mining and power capacity in India, China and Indonesia.

The Indian documents obtained by Climate Home reveal that the South Asian nation’s coal companies lobbied against regulations on fly ash pollution while expanding coal production at record speed.

In their correspondence with ministries, they said high fines for non-compliance with waste disposal rules were a risk to their financial sustainability and raised the prospect of coal-fired power plants being shut down, triggering a power crisis in the country.

Fly Ash Pollution

When thermal power plants burn coal for energy, the fly ash they generate as a byproduct is dumped in water-filled dam-like structures called dykes.

Old “legacy” dykes store ash from previous decades and are a major source of pollution for nearby communities, explained independent air pollution analyst Sunil Dahiya. Wet ash can leach into groundwater, while dry ash can blow away, causing air pollution and damaging crops.

Functioning disposal sites are also vulnerable to heavy rains, as they can overflow and pollute nearby settlements. This happened on at least three occasions between 2019 and 2021, according to a 2021 report by the NGO Fly Ash Watch Group.

To minimise the impacts of fly ash, companies can recycle it into products like bricks, cement sheets, panels and other construction materials – a process known as “utilisation”.

Sehr Raheja, climate change officer at the Indian think-tank Centre for Science and Environment (CSE), highlighted the need to utilise “legacy” ash given “the enormous quantity”, adding there are risks involved with it staying underground, such as water and soil pollution. As of 2019, the amount of accumulated unused ash in the country was about 1.65 bntonnes, according to a CSE report, with newer estimates suggesting even more, she said.

Controlling Pollution

Fly ash regulation – known officially as the Fly Ash Notification – has existed in India since 1999, but it was not until a 2021 update to the rules that fines were introduced for failing to comply with proper waste disposal, following the ‘polluter pays’ principle.

The regulation also imposed a mandate on thermal power plants to ensure 100% utilisation of accumulated old fly ash, as well as fresh ash produced by ongoing operations.

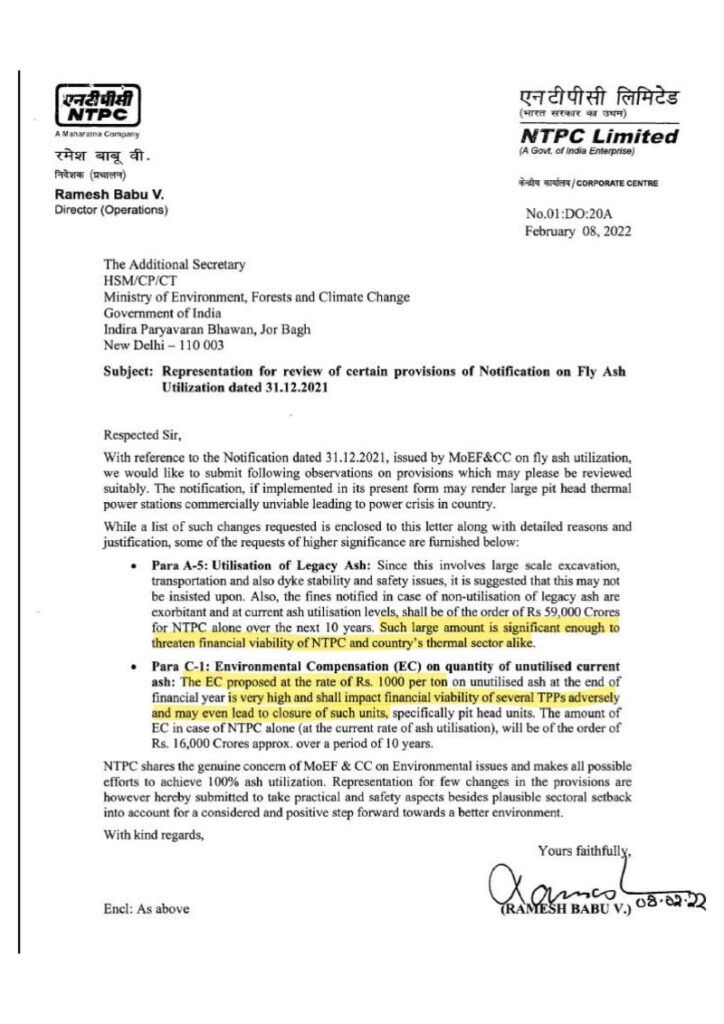

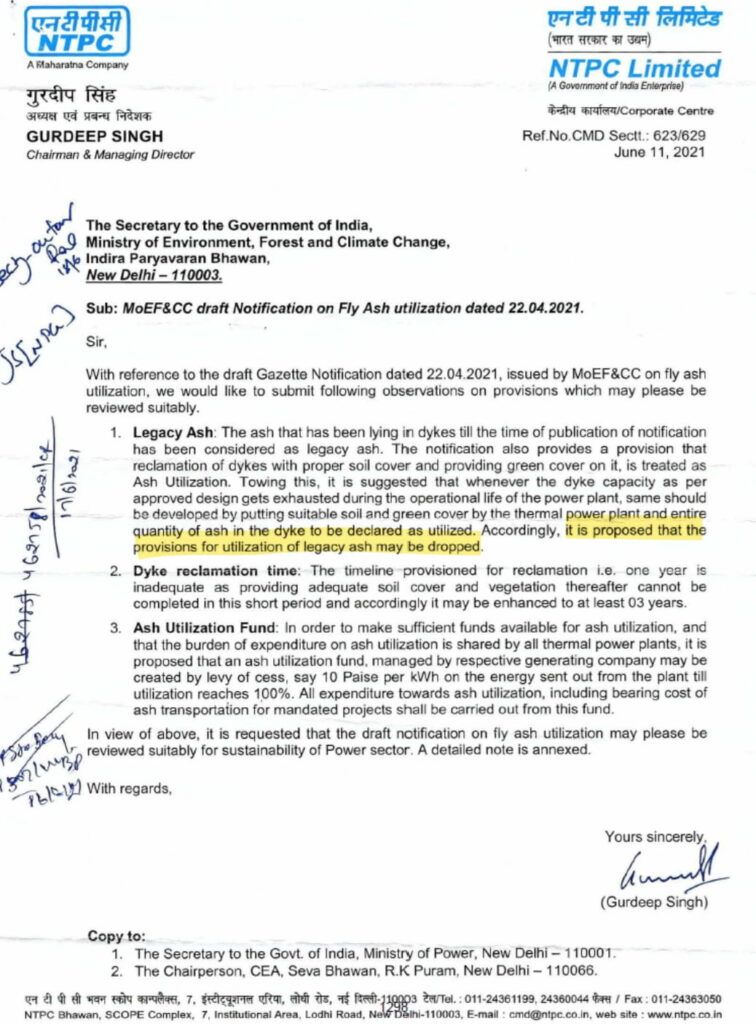

Documents accessed by Climate Home show that NTPC exchanged letters with government agencies asking for elimination of the mandate to clean up accumulated ash.

“It is proposed that the provisions for utilization of old legacy ash may be dropped,” reads a 2021 letter from NTPC to the Ministry of Environment, Forests and Climate Change.

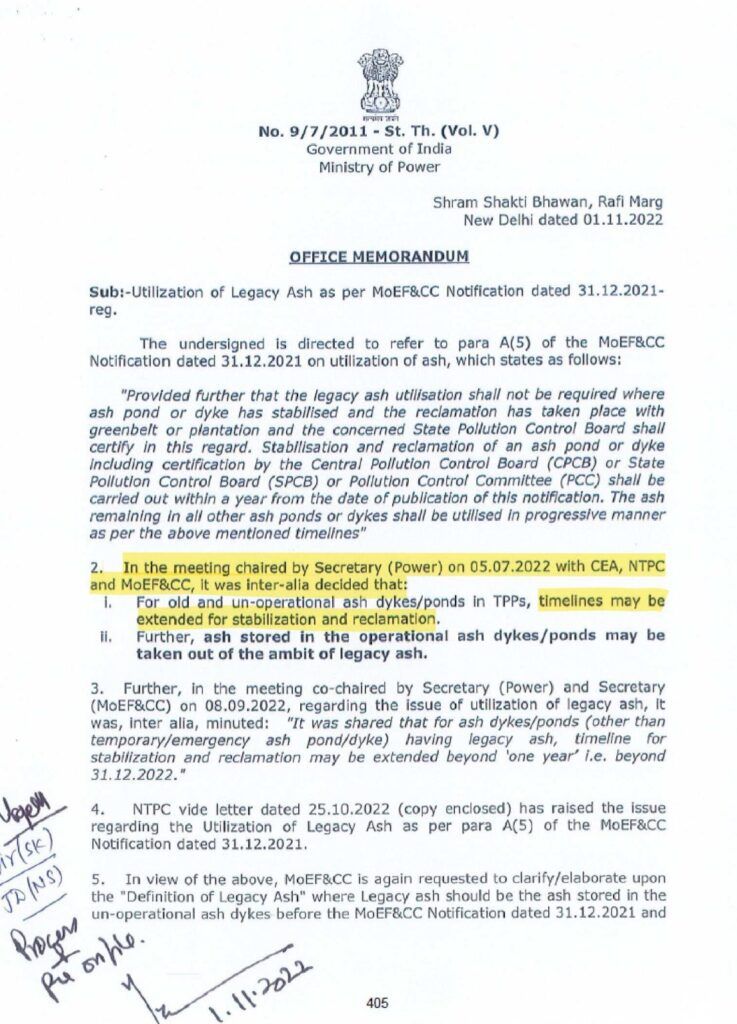

The 2021 rules were nonetheless passed, and they did introduce strict fines for coal companies. However, they also included what experts called a “loophole”.

The fly ash regulation exempted power plants from having to find a use for their old legacy ash as long as the ponds where it was stored were considered “stabilised”, meaning they had been secured against leakage. But the technical specifications of how that should be done were not defined, leading to concerns that arbitrary exemptions could be granted.

Yet even after these revamped regulations came into force in late 2021, lobbying intensified.

Persistent Lobbying

In 2022, NTPC was still concerned by a deadline of 10 years to utilise all legacy ash accumulated over decades, according to a letter addressed to the environment ministry. This would force them to transfer large quantities of fly ash to end users like brick-making kilns or ceramic product makers — or pay fines.

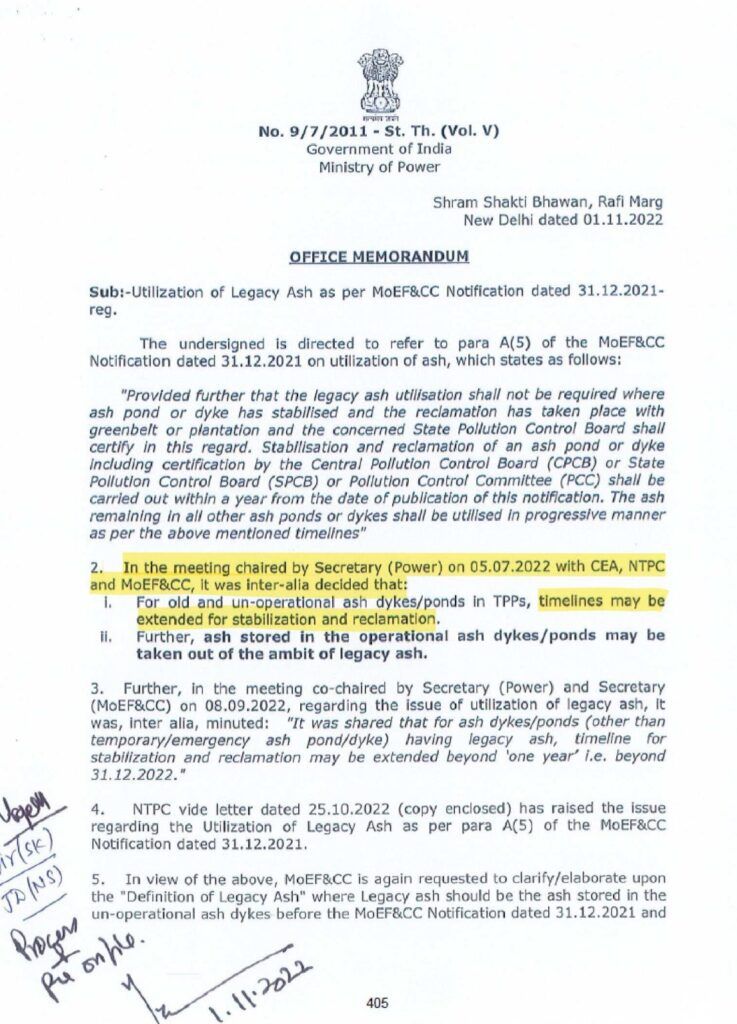

NTPC met with regulators at the Ministry of Power and agreed an extension to the period for stabilising old ash dykes from one to three years.

In the case of “operational” ponds, officials were persuaded not to label them as legacy ash, exempting them for the requirement for full utilisation. These changes were included in a 2022 amendment to the rules.

Shripad Dharmadhikary, who leads a civil society research group Manthan Adhyayan Kendra and has worked on fly ash management, said the unclear definition of stabilisation and longer timeframe for doing it provide “a loophole for power plants to evade use or proper disposal of legacy ash”.

The lack of technical parameters meant government authorities could struggle to guarantee that no more leaks would occur even if they certified the ponds, he added.

“Threat” to coal finances

The powerful companies also managed to limit the level of fines for non-compliance in a prolonged effort that began in 2020, when the first draft proposal on the new fly ash rules was circulated among coal companies.

That included a fine of Rs 1500 per ton, which was cut to Rs 1000 in the final 2021 rules after NTPC and other coal companies opposed it and asked for it to be removed entirely.

Even after this, executives from both Coal India and NTPC expressed alarm about the financial implications of the fines.

In a February 2022 letter to the Ministry of Environment, for instance, NTPC’s then director of operations Ramesh Babu V. wrote that the company could end up paying Rs 76,000 crores ($9 billion) over a decade – an amount “significant enough to threaten financial viability of NTPC and country’s thermal sector alike”. He warned the penalties could make large power stations at mining pit heads commercially unviable, leading to a “power crisis”.

Similarly, in a 2023 letter, CIL chairman and managing director Pramod Agrawal estimated that the “financial penalty” on only one of its subsidiaries (NCL) for failure to comply with the regulations could cost the latter Rs 38,145 crores (at least $4 billion) for just the 2022- 2023 financial year.

Coal expansion

However, the threats the executives outlined to the companies’ bottom lines do not seem to have translated into lower capacity to mine coal and produce thermal power, with both ramped up drastically during and after discussions on the Fly Ash Notification.

Expansion efforts were redoubled especially after an unprecedented power crisis in late 2021, which was attributed to logistical issues causing a shortage of coal supply.

In a January 2024 conference call with investors, NTPC’s management said it was considering awarding thermal power capacity of 15.2 GW in the near future, on top of the 9.6 GW thermal capacity already under construction for the group.

CIL, in its latest annual report, announced plans to increase coal mining capacity to 1 billion tonnes by the financial year 2025-26.

A previous investigation by Climate Home News showed that European asset managers had invested substantially in both NTPC and CIL, helping India’s coal industry to expand rather than phase down in line with international commitments.

Air pollution expert Dahiya said that, while India has lower historical emissions than countries in the Global North and requires flexibility to meet its energy needs, as well as international support to move away from fossil fuels, that did not mean coal companies should be “free to pollute”.

Raheja, of the CSE, said better controls on pollution are also a matter of justice for those living near coal-fired power plants.

“The environmental regulations are critically important for maintaining the health of the environment and of communities residing near coal facilities – even of people far away – as pollution, both through air and water, can be carried to a distance,” Raheja told Climate Home News.