“Death is your prince, you are not his patron.”

Zahira Rahman, writer and academic, remembers Hilary Mantel, the legendary novelist who chronicled Tudor history.

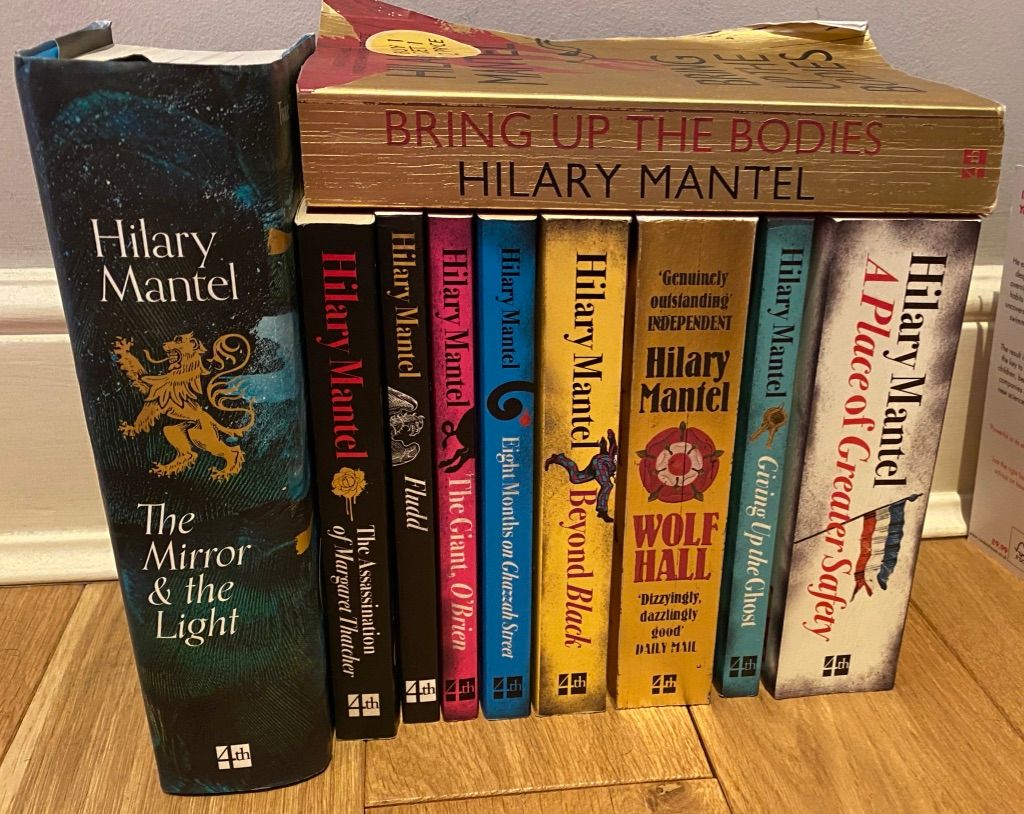

Hilary Mantel, the much-celebrated author of Wolf Hall, died at the age of 70. She passed away “suddenly and peacefully”, said a report in The Guardian. When I read this piece of news, I was reminded of the lines from her second Booker-winning novel Bring up the Bodies : “Death is your prince, you are not his patron; when you think he is engaged elsewhere, he will batter down your door, walk in and wipe his boots on you.” A brilliant chronicler of Tudor history, Hilar Mantel, who incisively and intimately sketched kings and queens in her famous trilogy _ Wolf Hall, Bring Up the Bodies and the more recent The Mirror and the Light _ seems to have chosen, as it were, the hour of her departure to almost coincide with the ascension of another monarch to the throne of England? So that she could avoid another dig at the powers that be. Like the one in these lines written by her: “the way we maltreat royal persons, making them one superhuman, and yet less than human”.

She was wary of drawing parallels between the royals of the present and those of the past. “I think simply because I prize the long view so much. And that’s why I won’t make the parallels. I think that if you do, it turns real people into these kind of fantasy figures and unfortunately, they’re not. They’re real, present and dangerous.” She is not in awe of the monarchy though she twice received recognition from the British Empire for her literary achievements. She is Dame Hilary Mantel. She made light of the recognition in her interviews talking about it as a bit of recognition for making an impact on culture. She said: “There’s no British Empire and it has no practical meaning.” She is fascinated by the machinations of Power and, for her, writing is all about exploring the human puzzle, not to solve it as in a mystery thriller. Her subtle questioning of the process of life and the complexity of its players is deeply political. She considers the act of writing an inherently dramatic activity, and not merely cerebral: “It uses up the whole of you.” She was described by her longtime agent as other-worldly who saw and felt things that we ordinary mortals missed. She talked of her novels as different from orthodox accounts of history and said “not because I know better but because I think differently.” She said her approach was similar to that of the theatre: “I am entering into a dramatic process with the characters rather than sitting in judgement on them.” She could be scrupulously honest and was known to be an intrepid researcher. Someone whose engagement with pain (from endometriosis which was left undiagnosed for years ) had helped in some sort of disappearing act -she studied law and worked as a social work assistant in a geriatric hospital- that saw her emerge triumphant after, with her astounding literary output . She says it was her chronic illness that made her a writer…” Because you have only a little bit of energy left and you have to ration it. ”

In one of her interviews, she spoke of an unhappy childhood that left her with traumatic memories of a strange household where her mother, father and her mother’s lover were living together and she went into a kind of hibernation to avoid being questioned constantly by the villagers. Her protagonist Thomas Cromwell, of whom she presented a starkly human picture, does not speak much too; it’s mostly the workings of his mind that the readers of the trilogy have access to. Far from a much-maligned historical figure, he emerges as a sensitive genius who lends his perceptive mind to the disturbed Henry VIII . Her beguiling narrative of Cromwell’s life is an engrossing tale of power. She said in an interview that Cromwell interested her because his whole project seemed unlikely. She talked of him as the man she met who wasn’t there: “You are concerned with the inner workings of someone who by definition is turned to the outside world and there is a limit to how much Cromwell knows himself.” Cromwell was a man with a vision, with grand plans that he led to fruition but his journey was so precarious that he was in terrible peril at each step. And “everything is in equipoise and one breath could destroy him.” The consequence of a mistake was calamitous, and you paid with your life. “I am, as I think a lot of authors are, concerned about the speed at which we are consuming history now, the way that the past, the very recent past, is being made into a version and real-life people walking around have to live with their representatives and so on”

The post-colonial nationalist in us has always been taught to hate the British and their monarchs and yet England and its history and landscape is always some returning memory for the postcolonial reader: Uncannily familiar.

Mantel’s record of the stories that have been displaced in space and time fascinate us forever because she plays on our need for, the struggle for, our “little meed for Power.”

“മരണം നിങ്ങളുടെ രാജകുമാരനാണ്, നിങ്ങൾ അവന്റെ രക്ഷാധികാരി അല്ല”

ഈ ലേഖനം മലയാളത്തിൽ വായിക്കുവാൻ ഇവിടെ ക്ലിക്ക് ചെയ്യുക.