The voice of the “Dilruba” – Pankaj Udhas

Bhupinder Singh, who was fondly addressed as Bhupiji by everyone in the section, was my senior colleague in the Railway Board, where I took up a job in the year 1981. Looking back, I see myself, in those days, as a naïve, eyes full of wonder, bursting- to-learn-more-about-everything-that-was-novel-to-me kind of person. You see, I had reached Delhi from a small town in the faraway coastal state of Kerala and the North of the country was too huge and too culturally different to absorb in one go.

Bhupiji epitomised all that strangeness I felt in the initial days of our acquaintance. His family had moved to Delhi during the partition, from a town in the undivided Punjab and had started life afresh in the capital city. He spoke of his childhood with nostalgia, when they would rush out to play with his friends, both Muslim and Hindu, his trouser pockets filled with dry fruits, stealthily stolen from his mother’s kitchen. He quoted Ghalib at the drop of a hat and I would stare at him, not understanding any of it, not even the simpler Urdu words in those couplets and he would exclaim with a kind of surprised exasperation, “Musalmaan hokar tum Urdu kaise nahi jaanti ho?!” (How can you be a Muslim and not know Urdu?) Bhupiji had done his entire schooling in the Urdu medium.

That would be my turn to educate him. All of us in Kerala, spoke only Malayalam, I would explain with a smile. “Kamaal hai!”(Surprising!), he would respond. From him I had learnt that the “g” sound in “ghazal” had to come out from the deeper part of the throat without the tongue interfering too much in its passage and that the structure of this genre of poetry was unique in that each couplet could stand on its own and make complete sense without having to depend on a continuity with the preceding or succeeding lines, although it would still remain associated with the whole. I am not sure if such a thing exists in poetry writing anywhere in the world. I am also not sure I can enunciate the word “ghazal” with all its tenderness even now.

But Bhupiji had got me hooked. And Pankaj Udhas was my personal pioneer into the realm of ghazal singing. I can’t really remember if it was Bhupiji or somebody else who told me about him and his very first album “Aahat” that had hit the market. Coincidentally, I had then got my first instalment of Dearness Allowance arrears. The year must be 1982. I had no idea about the concept behind that allowance or even what “arrears” meant, in terms of how it was calculated. But I was familiar with the term.

My father had been employed in the Civil Services Department of the State Government, with a salary that supported middle-class living, shorn of all indulgences. Splurging was not the norm. But once in every little while, he would come home in a buoyant mood and declare that he had got his D.A arrears. For him that meant a bottle of the more expensive brandy or whisky or whatever, that he would share with his friends in the late evening. For us kids, it meant a trip to the town for an ice-cream and “buttered buns” treat in “Kwality” or “Gopal Dairy.”

I guess my father had subconsciously passed on the message to me that D.A arrears were meant to be spent on something one likes and on which one would not normally spend money on. We used to get our salaries in cash, handed over the counter by the cashier, in those days. Thus it was that my friend and I decided to go to Connaught Place (CP) in the evening after office hours. C.P was not too far away from Rail Bhawan. We could take the same bus on the way back, as she stayed in R.K Puram and I was staying in Moti Bagh at that time.

Till then, I had not gone anywhere on my own, without being escorted by my husband, except to my workplace and back. I would have to inform him before he stepped out from his office, as that was an era before the advent of mobile phones. There was another thing which was equally or more important. Till then, I had dutifully handed over my salary to my husband for the running of the house. But this wasn’t salary, I figured. This was an allowance, and allowances were called for in spending it. Go for it, my mind urged enticingly. After two or three attempts at trying to reach him, I gave up, almost glad that I didn’t have to explain anything immediately.

Ah! The joy of holding that cassette in my hands! The secret satisfaction of flouting a norm, however insignificant that sounds now. My first conscious act of rebellion …and I have Bhupiji and Pankaj Udhas to be grateful to for that. Of course I had to face a very concerned and slightly pissed off husband. Where the hell was I gallivanting around without informing him?

The brief unpleasantness was soon behind me, to be followed by hours and hours of listening to that soft, smooth, silken voice on the cassette player, although some of the nuances of the couplets escaped my new Hindi learner’s repertoire of words.

“Tum aaye zindagi me toh barsaat ki tarah, aur chal diye toh jaise khuli raat ki tarah.” was not one of the difficult ones and it soon became my favourite in that album. Only “muntazzir” and “jazbaat” and “ehad” got me wondering, but there was always Bhupiji to help me out. I have to confess here, that I had no knowledge whatsoever of the poets who had written the lyrics for those songs. Pankaj Udhas sang it as if he had written the lines dipped in romance and the pangs of separation himself and that is all that mattered then.

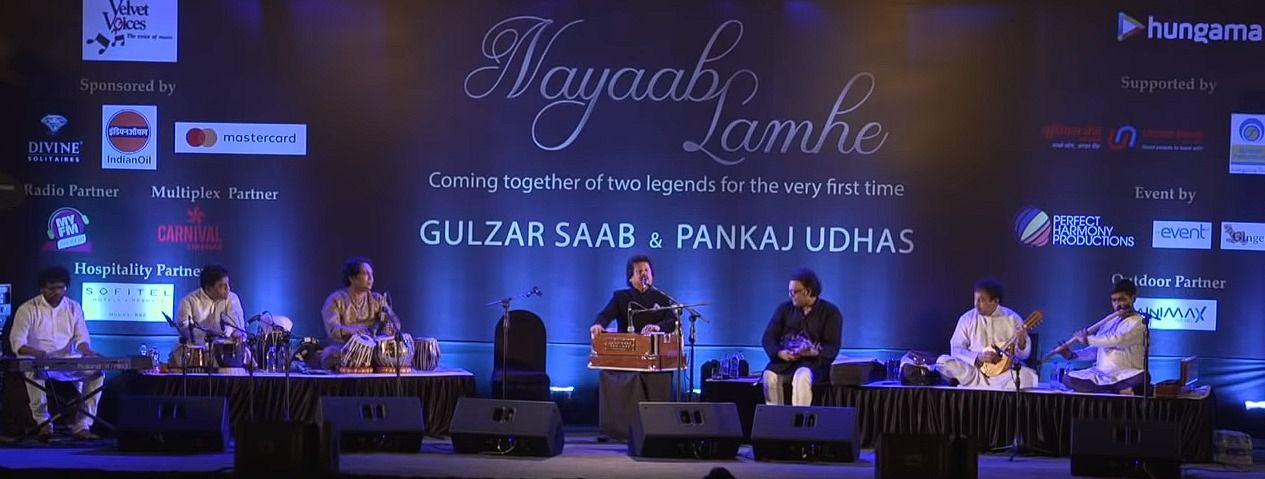

Later on, of course, “Chitti Aayi hai” would take the music world by storm and evoke intense nostalgia in the hearts of all those who had left their mother’s hearth and home in search of greener pastures. By then, Pankaj Udhas, who had left the country and gone to Canada in order to carve out a career for himself (not as a singer) had incidentally got some opportunities to perform before very receptive audiences and had then gone on to give one concert after another in that foreign land and establish his name as a ghazal singer. May be the yearning for his native land, in those days when he was away from it, had added the extra sentimental texture to that song, which he got to sing in “Naam” a film directed by Mahesh Bhatt, a few years after his return to India. He had sung for several other films after that, all of them very popular.

Another one of the Pankaj Udhas ghazals that has always been my personal favourite, is “Aye ghame zindagi…kuch toh de mashwara.ek taraf uska ghar, ek taraf maikada”, expressing the eternal dilemma of being torn between two equally tempting destinations, symbolised by the beautiful lover on one side and the tavern on the other. “Meikade me kabhi pahunche toh kho gaye….. chaon me zulf ki kabhi hum so gaye” (If at all I reached the tavern, I would lose the shade of her tresses under which I slept) and “ zindagi ek hai aur talabgaar do, jaan akeli magar, jaan ki haqdaar do” (One lifetime and claimants two …one life and two entitled to it). That ghazal beautifully evoked the desperation of the heart that is ripped asunder by conflicting emotions, whenever Pankaj Udhas gave voice to it.

The journey from being that little lad in Charakhadi village of Jetpur in Gujarat, who sat beside his father, Keshubhai Udhas, listening engrossed as he made the strings of the “dilruba”( the word dilruba means, that which ravishes or steals the heart) come alive with melodies, to the nine-year old who sang “aye mere watan ki logon “ in front of an audience after the Indo-China War, to the long-haired and bell-bottomed youth of St. Xavier’s College in Mumbai, who entertained his friends in the college canteen with his singing, to the love-struck Romeo who went around wooing his sweetheart Farida, who belonged to the Parsi community (these lovers fortunately were not star-crossed and they did marry eventually with the blessings of both families and had two daughters to complete their beautiful bonding), to his temporary migration to the West and subsequent return after making a name for himself in the world of ghazal singing and in playback singing for Bollywood movies and going onwards to stamp those spaces with the seal of his own style, has been long.

But it was not just the music. He was a great human being, as people who knew him closely vouched for. He always believed in giving back some of that which he felt he had been bountifully blessed with…encouragement from his parents and his two elder brothers, Manhar Udhas and Nirmal Udhas, both of whom are also singers, opportunities to express his talent and financial security and endless love from music lovers.

His talent –scouting television programme on Sony TV, “Aadab Arz Hai” gave a stage to many young aspiring ghazal singers. So too did the Khazana Ghazal Festival. This music festival had in fact been started by the music label “Universal” project and had been discontinued after five years. It was Pankaj Udhas, Talat Aziz and Anup Jalota who got together and revived it. Pankaj Udhas had already been involved with the “Parents Association: Thalassemic Unit Trust (PATUT)” in Mumbai and Cancer Patient’s Aid Association (CPAA). It was he who suggested that the concerts be held as fund-raising events and the proceeds from the festival be given to both these Associations. The festival was being held annually since then, from the early eighties.

There is a ghazal in the first album, “Aahat” (sound of footsteps) of Pankaj Udhas which seems to be echoing over all the other countless songs and ghazals that he had rendered in his lifetime…. a voice of angst that he surely must have felt when he chose that for his first album. Very symbolic of our times, it seems. The lyrics are by Namwar, well known literary critic, and academician from Uttar Pradesh.

“Ab to insaan ko insaan banaya jaaye, Ya koi aur hi bhagwaan banaya jaaye”

(It is time now to make a human being of Man, Or else, to create another God)

“Rahnuma khud ko sabhi paak saaf kahte hain, Aaina kisko yahan kaise dikhaya jaaye?”

(The guides all declare themselves to be pristine and pure, To whom and how do we hold up a mirror?)

“Log chhip chhip ke yahaan roz bika karte hain, Shart hai mol ko chupke se bataaya jaye”

(Clandestinely, people here are selling themselves daily, Will anyone dare to disclose even privately, at what price?)

I would like to wind up this tribute to a much liked human being and singer, by cocking a snook at Bhupiji.

You see, in those days, for the people in North India, everyone hailing from South India was a “Madrasi.“ We from Kerala, who held the palm frond laden stretch of land very close to our hearts, used to get ruffled with this loss of our distinctive ethos and language and culture. Every region has that, isn’t it and those loyalties will always remain, I guess. Well, we who wound up in the North would eventually learn Hindi and assimilate their ways into our daily lives, more or less. But one always felt that the reverse was not always true.

Pankaj Udhas singing in Malayalam was a kind of sweet revenge in a strange way. Yes, he did and it is a beautiful song, composed by Jithesh, who hails from Thalassery in the North of Kerala. The lyrics for this were written by Rafeek Ahmed, who has lent his lines for many of the most popular songs in Malayalam films. Rafeek Ahamed is a recipient of several awards including many awarded by the State and Central Governments for his contributions to poetry and songs in Malayalam films. Jithesh is a disciple of Anup Jalota and it was in the ghazal album titled “Ennum ee swaram” (Always, this voice) that both these singers, Anup Jalota and Pankaj Udhas, had contributed a song each.

“Ee nilaavil peytha manjil, kettu njaan ninn swaram, ninn su swaram

Ormmakal thann thanthi thorum meetti njaan ninn swaram, ninn su swaram” goes the lyrics of the ghazal sung by Pankaj Udhas.

“I hear your voice, your beautiful voice in the dew drops that fall in this moonlit night. Softly, I strum the strains of your voice, your beautiful voice, through the strings of my memories”

So, his “aahat” will continue to echo in this part of the peninsula as well, in the language of the monsoon winds blowing in from the Arabian sea, when it hits the shores, just like the notes that floated around to his ears from his father’s “dilruba”.