A Native Mahatma of Communication

“ To be true to my faith therefore, I may not write in anger or malice. I may not write idly. I may not write merely to excite passion. The reader can have no idea of the restraint I have to exercise from week to week in the choice of topics and my vocabulary. It is training for me. It enables me to peep into myself and to make discoveries of my weaknesses. Often my vanity dictates a smart expression or my anger a harsh adjective. It is a terrible ordeal but a fine exercise to remove these weeds.” – ‘Young India’ {July 2, 1925}

“ To be true to my faith therefore, I may not write in anger or malice. I may not write idly. I may not write merely to excite passion. The reader can have no idea of the restraint I have to exercise from week to week in the choice of topics and my vocabulary. It is training for me. It enables me to peep into myself and to make discoveries of my weaknesses. Often my vanity dictates a smart expression or my anger a harsh adjective. It is a terrible ordeal but a fine exercise to remove these weeds.” – ‘Young India’ {July 2, 1925}

The above passage provides an insight into the success of one of the master communicators in the history of humanity. To truly grasp the magnitude of Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi’s unique feat in uniting and then galvanising crores of the unlettered into the non-violent struggle for independence in that pre-web, pre-mobile era, is to marvel at the near impossible. To evaluate Gandhi in a historical perspective it would be instructive to consider briefly the major social upheavals that have transformed our modern world.

Late eighteenth century France witnessed the overthrow of an insensitive monarchy. Despite the conflagration of mass discontent, the actual action in this upheaval involved a revolutionary vanguard numbering a few thousand, mostly from Paris. Once the fuse was lit with the storming of the Bastille in November of 1789, the movement raged in an incohesive manner across the land, shorn of a centralised leadership. The divisions that emerged among the Jacobin power coterie led to the ghastly phenomenon of the sons of the revolution – Mirabeau, Marat, Danton, Robespierre, St. Just and Carnot – devouring each other. Perhaps the moment of the most bloodthirsty turn was the guillotining of Georges Danton, after he fell out with his onetime comrade-in-arms, Maximilien de Robespierre. To his executioner, Danton’s defiant words were: “Show my head to the people. It’s worth the trouble.” Within four months Robespierre himself would have his head lopped off by in the Thermidorian reaction and from this chaos would rise a dictator in the form of Napoleon Bonaparte.

Words were drowned in blood. The Russian Revolution had a more committed leadership sharing a congruence of ideological interests, than those who led the French Revolution. In the aftermath of the Czarist system crumbling post-First World War fiasco, the time was ripe, for the Bolsheviks under Vladimir Ilyich Lenin to swiftly seize the levers of power and overthrow the vestiges of a decadent imperial state. The communist party concentrated on capturing power and power alone. A great swathe of humanity was destined to fall prey to the juggernaut which sought to re-fashion society under the megalomaniac boot of Joseph Stalin. The thrust for refashioning society was indeed in the name of the people, but ultimately it led to their own detriment. Communication was not a factor in the Stalinist era.

The Chinese Revolution bellowed into a roaring inferno driven by Mao Zedong, tempered through the arduous decade-long campaign of the Long March, which could be termed as a sort of combative ‘padayatra. A padayatra that aroused the suffering peasantry dissatisfied with an inefficient Kuomintang regime, which had replaced the earlier infructuous administrative system. It was a period marked by the Japanese occupation of most of the Chinese mainland. Mao turned this occupation into an advantage, perfected the art of guerrilla warfare to inflict ‘death by a thousand cuts,’ in a modern adaptation of the classical martial strategy prescribed by Sun Tzu. If in Russia, it were the workers who rallied to the cause, here it was a compact mass of peasants who embarked on a great revolutionary endeavour, the victorious bands gradually coalescing to form the People’s Liberation Army. The call to arms was direct action, theories and theorising would come later.

If violence, blood-shed and fraternal wars were the hallmarks of these three defining transformations which stamped their imprint on modern human history, the Indian freedom struggle predicated on non-cooperation was a unique movement in the annals of all freedom struggles. Gandhi discovered the moral power of this non-violent soul force faced with draconian laws of Jan Smuts’ apartheid regime in South Africa. (incidentally Smuts outlived Gandhi by two years). Here it would be relevant to ponder on how uniquely among leaders, Gandhi alone had the moral fibre not to allow a crowd to descend into a mob, which is what the Hitlers and Mussolinis did.

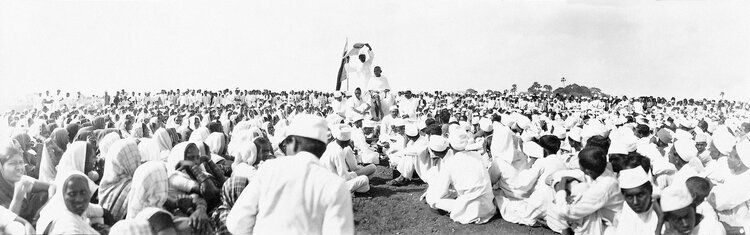

The potential for murderous violence inherent in this phenomenon is best encapsulated in Elias Canetti’s immortal formulation: “After the destruction, the crowd and the fire die away…” (Crowds and Power p. 21, Penguin books, 1973}. But Gandhi pacified the crowd through his well attended prayer meetings and channelised the massed energy into passive acts of resistance. In those formative years Gandhi realised the importance of communication to mobilise public opinion on social issues. He also realised that it was a means of reaching across to an unsympathetic administration.

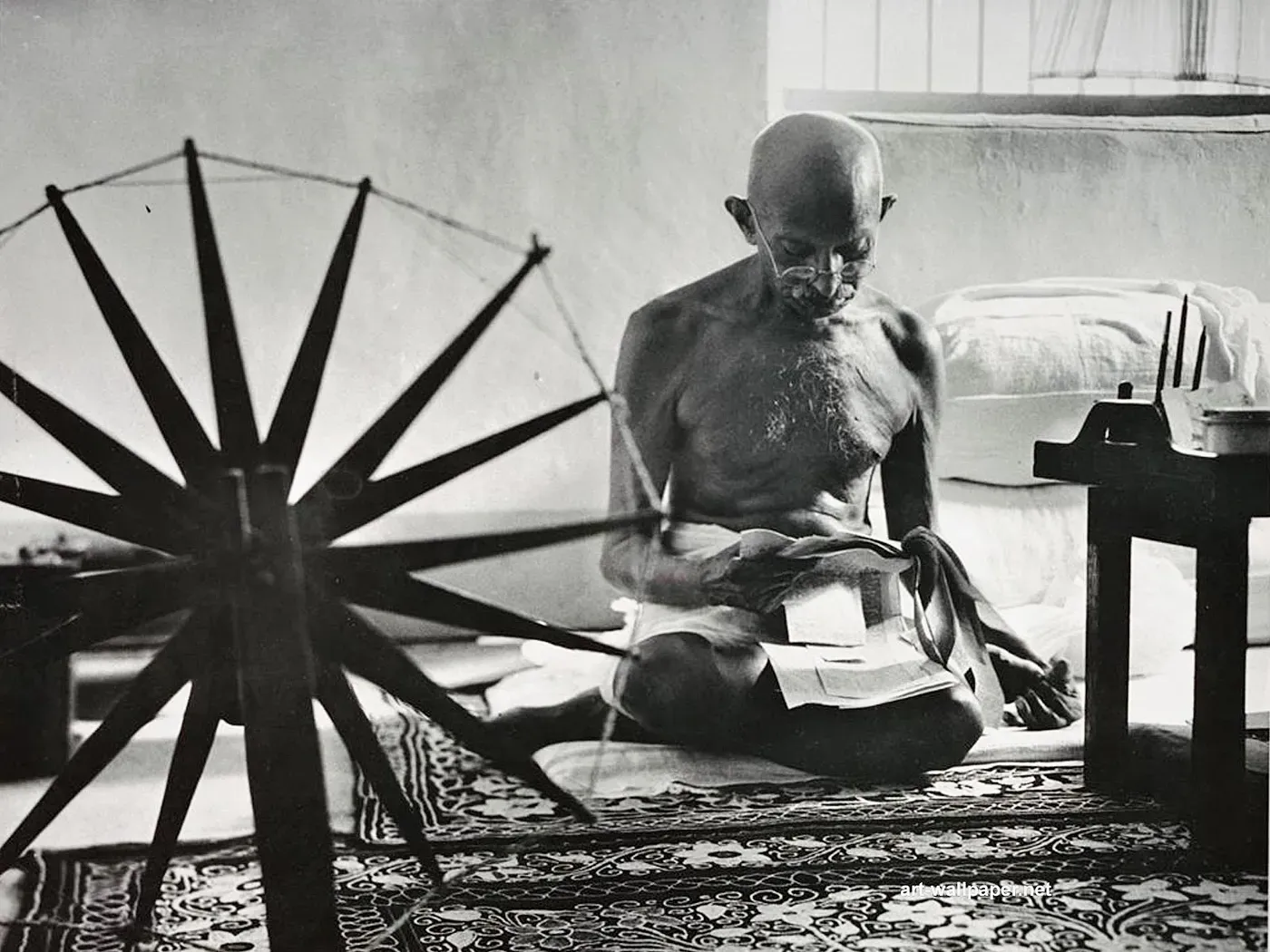

Thus in 1903, he established a 16-page tabloid, ‘Indian Opinion’, issued every Saturday to educate the political masters on Indian grievances and rally support for the community’s’ causes. He took over as editor from Mansukhlal Nazar, also the then secretary of the Natal Congress, in 1904. He continued as editor till 1914. This was the first of six publications he would be associated with for forty years of his life, three of which he would edit. Its significance in Gandhiji’s life can be gleaned from this revelation in ‘My Experiments with Truth’: “Indian Opinion… was a part of my life. Except for the intervals of my enforced rest in prison there was hardly an issue of ‘Indian Opinion’ without an article from me. Indeed the journal became for me a training in self restraint and for friends a medium through which to keep in touch with my thoughts.” It was bi-lingual, in English and Gujarati. For some time it appeared in Hindi and Tamil as well.

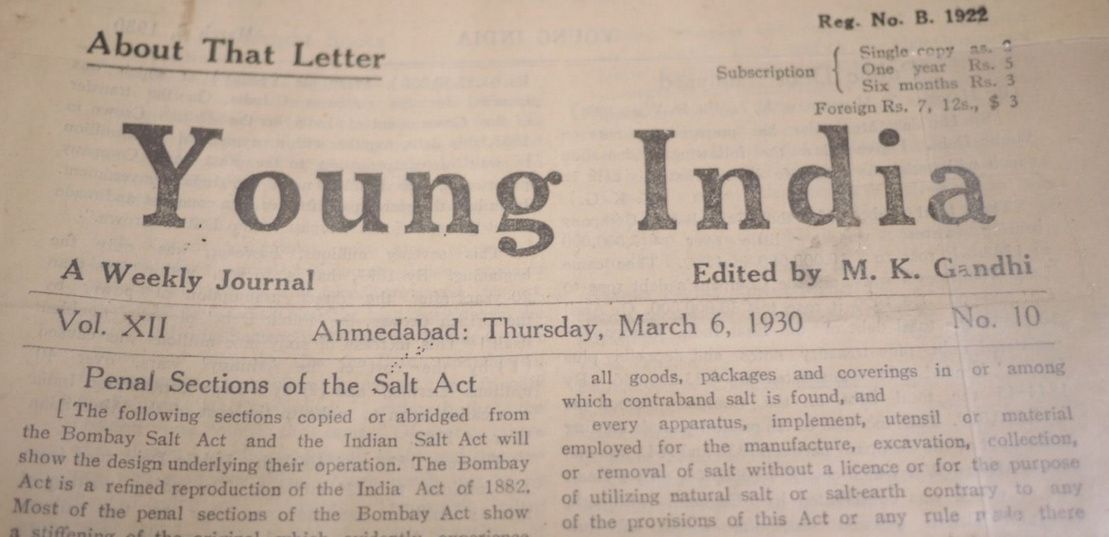

Gandhi launched ‘Young India’, English weekly in 1919, which ran till 1932. ‘Navjivan’, another weekly was launched the same year, and both were used by him to air his views and to educate people on Satyagraha. In 1933 he started ‘Harijan’, ‘Harijanbandhu’ and ‘Harijansevak’ in English, Gujarati and Hindi, respectively. These carried his crusade against the social evil of untouchability. The manifold facets of rural poverty too were highlighted in these publications. As he wrote in ‘Young India’ of July 2, 1925: “I have taken up journalism not for its sake but merely as an aid to what I have conceived to be my mission in life. My mission is to teach by example and present under severe restraint the use of the matchless weapon of satyagraha which is a direct corollary of nonviolence.” He was to later successfully develop these into individual and collective acts of non-violent non-cooperation against the mightiest colonial power in history.

Of these, the act of individual ‘satyagraha,’ would prove to be a formidably unique act of resistance, as it pitted the soul force of one human being against the assembled might of the state. This model will have increasing relevance, like the rest of Gandhiji’s teachings, in a highly asymmetric world, fraught with the inequality predicament. Gandhiji’s approach to editorial freedom is epitomised by his response to the rebuff he faced from his editorial colleagues in ‘Harijan’, who refused to publish certain portions of his prayer speech dispatched in February 1947 from Naokhali. Though he wired to assure them that he was prepared to take the entire responsibility for publishing the full text of his speech, it was never published.

Only a truly magnanimous soul could have written as Gandhi wrote without the least bit of rancour to one of the trustees: “I fully realise ‘Harijan’ does not belong to me. It really belongs to you who are conducting it with such diligence. Whatever authority I exercise is moral.” The subtle rebuke, the equivalent of a moral slap on the wrist, is a reminder of his role as an exemplar of morality. He was particular that “Newspapers are meant primarily to educate the people. They make the latter familiar with contemporary history. This is a work of no mean responsibility. It is a fact, however, that readers cannot always trust newspapers. Often facts are found to be quite the opposite of what has been reported. If newspapers realised that it was their duty to educate the people, they could not but wait to check a report before publishing it. It is true that often they have to work under difficult conditions. They have to sift the true from the false in a short time and can only guess at the truth. Even then, I am of the opinion that it is better not to publish a report at all if it has not been found possible to verify it.” This accent on cross-checking facts is the basic tenet of journalism, which is increasingly abandoned in a cavalier fashion in our age of visual media and social media theatrics.

Gandhi addressed a bewildering variety of constituents; freedom fighters and politicians, women, students and minorities, writers and thinkers, slum dwellers and villagers, farmers labourers and illiterates, as well as those belonging to various religions, castes and communities. To complicate matters further he would not fashion his thoughts and statements to suit the taste of his audience. On the contrary he would utter uncomfortable truths unpalatable to certain sections, or worse, those that were even incomprehensible to the masses. This was quite in keeping with the fact that he was not just the leader of a freedom movement, but a social reformer too. Genuine leaders bend the moral arc of history to their sagacious conscience.

Thus for example, he had the ethical authority to foreground the issue of ‘polluting touch,’ much to the discomfort of upper castes, to whom untouchability was a social reality and part of the traditional status quo, best left unchallenged. People followed him, even when they did not see his point or grasp its significance. His style was lucid, even while passionately championing public causes. Gandhi’s journalistic aim was to tap into the popular mood and give voice to it. Fearless exposure of injustices and administrative failings was another feature of his journalism. But he was a stickler for truthful reporting and was never impolite, instead was always moderate in his use of language. And if he erred, he did not hesitate to confess it.

Gandhi never indulged in the journalistic evil of irresponsible criticism. His subject matter was wide-ranging and invariably his solutions to social issues were informed by his unique understanding of Indian reality within the over-arching framework of ethics. One rhetorical device that Gandhi used effectively, like most effective journalists, was the rhetorical question, as in this extract: “The Qaid-e-Azam says that all the Muslims will be safe in Pakistan. In Punjab, Sind and Bengal we have Muslim League Governments. Can one say that what is happening in those provinces augurs well for the peace of the country? Does the Muslim League believe that it can sustain Islam by the sword?” {Speech at a Prayer Meeting, Sept 7, 1946}. Or in this instance: “What good will it do the Muslims to avenge the happenings in Delhi or for the Sikhs and the Hindus to avenge cruelties on our co-religionists in the Frontier and West Punjab? If a man or a group of men go mad, should everyone follow suit?” {Prayer Meeting, September 12, 1947}. He also employed irony to devastating effect. “I believe myself to be an orthodox Hindu and it is my conviction that no one who scrupulously practices the Hindu religion may kill a cow-killer to protect a cow.” {On “Hindu Muslim Unity”, April 8, 1919}. Or “Let not future generations say that we lost the sweet bread of freedom because we could not digest it.” {Prayer Meeting, September 12, 1947}.

His coruscating sarcasm scorched even the high and mighty. Churchill sneered: “It is alarming and also nauseating to see Mr. Gandhi, a seditious Middle Temple lawyer of the type well-known in the East, now posing as a fakir, striding half naked up the steps of the Viceregal palace to parley on equal terms with the representative of the King-Emperor.” Later, when somebody asked Gandhi on him meeting King George V thus attired, he famously replied: “The King had enough for both of us.” Churchill was the collateral damage in this gentle barb. Gandhi’s devastating take down on the ‘plus-fours’ sartorial culture of the British was the description of his dressing as ‘minus-fours.’ But he reserved the distillation of his phosphorescent wit for a hapless reporter, who sought Gandhi’s opinion on Western civilisation: “I think it would be a good idea.” This withering assessment might never be bettered!

Even in the face of provocation his language remained polite, as is evident in the manner of his response to Churchill’s harsh remarks on the post-Independence violence in our subcontinent: “Mr. Churchill is a great man… He took the helm when Great Britain was in great danger after the Second World War started. No doubt he saved the British Empire from a great danger at the time. If he knew that India would be reduced to such a state after freeing itself from the rule of the British Empire, did he for a moment take the trouble of thinking that the entire responsibilities for it lies with the British Empire?” {p.143, The Good Boatman: A Portrait of Gandhi by Rajmohan Gandhi, Penguin 1995}

Gandhi’s language was free from hatred. As he always made clear, his righteous fight was against British imperialism and not against the British people. This aspect is perhaps exemplified in how he could communicate with the textile workers of Lancashire who were adversely impacted by his call to boycott foreign cloth, and still win over their sympathy. Gandhi’s deep connect with the masses was also achieved through the idiom he embraced, which had always resonated in the collective unconscious of the Indian mind. He successfully exploited the common man’s belief system, their fondness for myths and innate religious orientation; thus the use of ‘ram raajya’ for the ideal state; ‘harijan’ to refer to the traditionally disadvantaged; ‘satyaagraha’ for non-violent agitation against the oppressor, and the like.

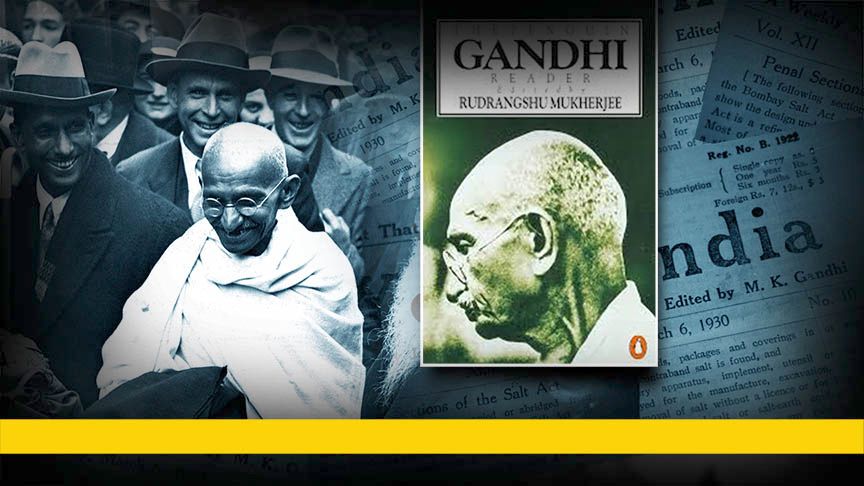

Gandhi chose to express himself in Gujarati, Hindi {or Hindustani, as he would have it} and English. The choice of the language was dictated by who he was addressing. He believed that English was not in the best interests of India, because it was and would always be elitist. “Our English speech,” he said, answering a student on Dec 12, 1925, “has isolated us from the millions of our countrymen. We have become foreigners in our own land.” But, true to his character, he qualified this opinion with: “I have profound admiration for the English language and many noble qualities of the English people…” {p. 285 The Penguin Gandhi Reader ed. Rudrangshu Mukherjee 1993}. Though Gandhi penned only a few books, his innumerable articles and interminable correspondence eventually filled the pages of the 90-volume Collected Works, published posthumously by the Indian Government. It is also estimated that during his lifetime Gandhiji wrote more than 1 crore words, translating into 500 words every day for 50 years! Gandhi truly was thus a native Mahatma of communication also!