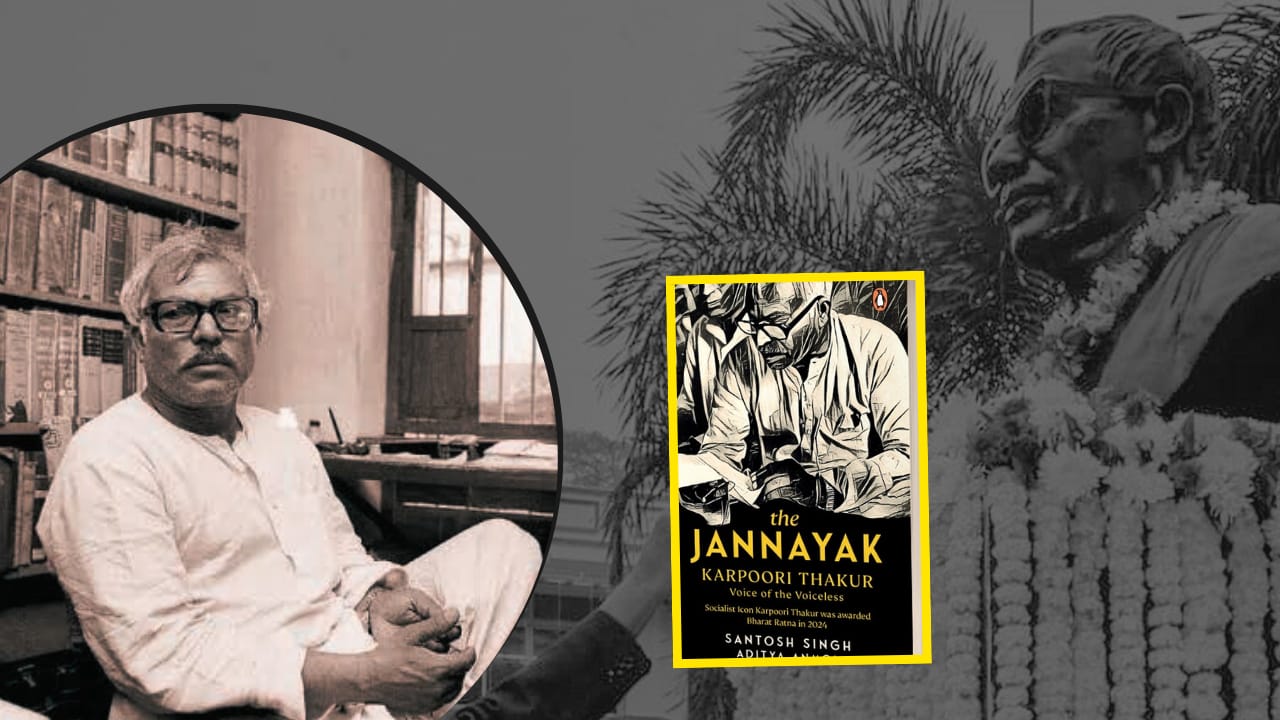

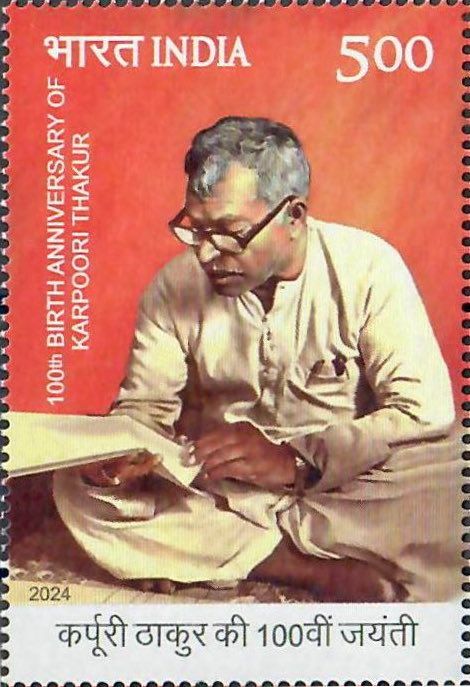

The following is the Review of the Book ‘The Jannayak Karpoori Thakur: Voice of the Voiceless’ authored by Santosh Singh and Aditya Anmol (Published: May/2024, Penguin Random House India)

There are many reasons to remember the legendary Indian political leader Karpoori Thakur. However, if one were to single out one reason to highlight his legacy, it would have to be the reservation policy for marginalised classes in the government jobs, a move that dramatically impacted Indian history and the people of the country. Summed up in simple terms Karpoori Thakur’s life could be described as follows: This man born in the nondescript Pitaunjhia village of Samastipur District of Bihar, in the marginalised Nai (barber) community, which had little social clout and had only minuscule presence in the State’s cities and villages, was the original progenitor of the movement for social justice in North India. Bihar became the first state, during Thakur’s second stint as the State chief minister (in 1978), to reserve a 26% quota for the ‘socially disadvantaged’ groups in the jobs.

It was a pioneering initiative in many ways. It recognised the heterogeneity among the backward classes at that stage of history itself. The Thakur-led cabinet allocated a 12% quota for the extremely backward classes (EBCs) and 8% for the other backward classes (OBCs). The women and poor among the upper castes got 3% quota each highlighting the inclusive vision of Thakur.

The enduring legacy of Thakur is evident from the fact that reservation has emerged as a central issue to counter the hydra-headed Hindutva that the ruling Sangh Parivar represents today. If there was one issue that worked for the Congress and Socialists organised under the larger banner of the Indian National Developmental Inclusive Alliance (INDIA) to reduce the Narendra Modiled Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) to the minority status in the 18th Lok Sabha, it was the slogan highlighting the ‘threat to the Constitution” that the marginalised sections perceived as a threat to the reservation policy. Moreover, the verdict of the 7-judge Constitution Bench of the Supreme Court on the categorisation of the scheduled castes and scheduled tribes has engaged political parties, public intellectuals and policymakers of all hues in analysing its larger implications on India’s polity and society.

And, if Karpoori Thakur was the pioneer of the job quota system, The Jannayak Karpoori Thakur: Voice of the Voiceless (Penguin Random House-2024) authored by Santosh Singh and Aditya Anmol is, by all accounts, the best source to understand the gamut of the reservation scheme implemented by the Janata Party government in Bihar 46 years ago.

“Pioneering Quota Politics” is, understandably, the largest chapter of the 330 page book. The chapter is comprehensive. It has covered the minute details about the process through which this landmark initiative was moved forward. It elaborates how Karpoori Thakur, despite violent opposition from the upper castes, navigated the legislation through very many obstacles, including the age-old grip of the adherents of the varnashram system on the society as a whole and the stranglehold it had created on the social psyche of that period. The dominant stream of society at that period -and arguably even now – was the Brahmanical society which the Sangh Parivar interprets as ‘Hindu society’ or ‘Sanatan’ society.

The Bharatiya Jan Sangh, which was the political instrument of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) led Sangh Parivar till 1977, and was succeeded by the BJP in 1980, was a part of the Thakur led Janata Party government in 1978. Kailashpati Mishra—the pioneer of the Hindutva politics in Bihar—was the finance minister in that government. As the book rightly explains, an otherwise sober and soft-spoken Mishra, opposed many of Thakur’s initiatives. The Congress was in the opposition at that time and for obvious reasons it opposed the then ruling coalition led by Thakur.

The book also highlights the ironical and self-contradicting stance of a large number of the upper caste political leaders of that period. A sizable section of them were part of the Socialist stream right from the beginning of their political career or had joined the Janata Party after defecting from other parties. However, they did not understand or imbibe the socialist and revolutionary character of Thakur’s initiative and were found to be visceral in their opposition to the efforts of the leader to strengthen an affirmative action policy as enshrined in the Constitution.

Thakur’s initiative was rooted in the larger goal of socialism propounded collectively by Karl Marx, Mahatma Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru, B. R. Ambedkar, and Ram Manohar Lohia. But, most of the upper caste leaders in the Janata Party—a conglomeration of anti-Congress parties of that time—opposed Thakur. These leaders coined abusive slogans to rundown Thakur’s pedigree. The book has highlighted all these in a detailed manner.

Thakur’s action eventually cost him the Chief Minister’s chair with another Socialist leader belonging to a scheduled caste, Ram Sundar Das replacing him in 1979. Though Das belonged to a scheduled caste, the upper castes were comfortable with him mainly because he guarded their interests vested in varnashram system. The towering exception among the upper caste leaders was Chandra Shekhar, the then President of the Janata Party.

Why Chandra Shekhar, who went on to become the Prime Minister in 1990, is regarded as “exceptional” is essentially because of his unflinching support to Karpoori Thakur in those cataclysmic times. Wading through the political rough and tumble of that period as well as the mayhem created by some of his own caste-men, including former Bihar Chief Minister Satyendra Narayan Sinha, Chandra Shekhar stood solidly behind Karpoori Thakur. The ‘Adhyaksh ji’, as most of his Socialist contemporaries referred to him, Chandra Shekhar bestowed Thakur with the sobriquet of “Jannayak”.

Despite the disintegration of the Janata Party later, the Jannayak salutation is still used among the present generation of democrats and socialists, who follow the political legacy of that historical political party, to refer to Thakur. The book also traces the details of the freedom struggle and farmers movement as well as other agitations and peoples movements against feudalism. This explains the historical setting in which Karpoori Thakur was born and fought his way up through social and political challenges to grow into a mass leader.

My only criticism of the book and that is a major one is that it has sought to link Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s personality and initiatives with that of Thakur. The authors have used the current Union Defence Minister Rajnath Singh’s interpretation to draw a parallel between Thakur and Modi, based on the birth of the two leaders as well as their vision and lifestyle. It amounts to oversimplification, which should have been avoided. Of course, the Modi government awarded ‘Bharat Ratna’ posthumously to Thakur ahead of the 2024 Lok Sabha elections, providing greater topicality to the book. But comparing the Modi government’s move to award 10% quota to economically weaker sections (EWS) and Modi’s birth in a backward caste with Thakur’s life and worldview hardly adds to the overall value of the book.

Despite this aberration, I would recommend the book to everyone desirous of understanding the sociology, politics and modern history of Bihar. It provides for light reading adorned with enchanting anecdotes. It is a delight for political reporters as the book has largely been written in a classical reporter’s style. Reading the book, one also gets a bird’s eye view of the 1917 Bolshevik revolution, which led to the formation of the USSR and the myriad people’s movements in Eastern Europe of the early 20th century and beyond.