A Chronicle of Prime Ministers Down the Years

A review of veteran political journalist Neerja Chowdhury’s recent book ‘How Prime Ministers Decide’

This book is a must-read for anyone interested in in-depth information of the politics of India from the late 1970s to the middle of the 2010s. It starts with the post-Emergency elections of 1977 and ends around 2014, when Narendra Modi assumed office as Prime Minister. It gives the reader a wholesome understanding of the shape of Indian politics of this period and its essence.

In 1977, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi called elections in January when she had no reason to do so – the Emergency regime was running smoothly on the surface; the tenure of the Lok Sabha had been extended (thoroughly unconstitutionally) by another year until 1978; she had given priority to the implementation of her 20-point Programme, which was a ready excuse to continue with her government and she needed time to groom her wayward son Sanjay Gandhi for a larger political role. Yet she took a leap into the dark and called the elections after releasing her opponents from prison. Why did she do it? Neerjah Chowdhury throws light on the possible reasons, mainly zeroing in on the fact that Indira Gandhi felt that she was riding a tiger which she could not dismount and that Sanjay was becoming uncontrollable, especially with his family planning and slum clearance drives.

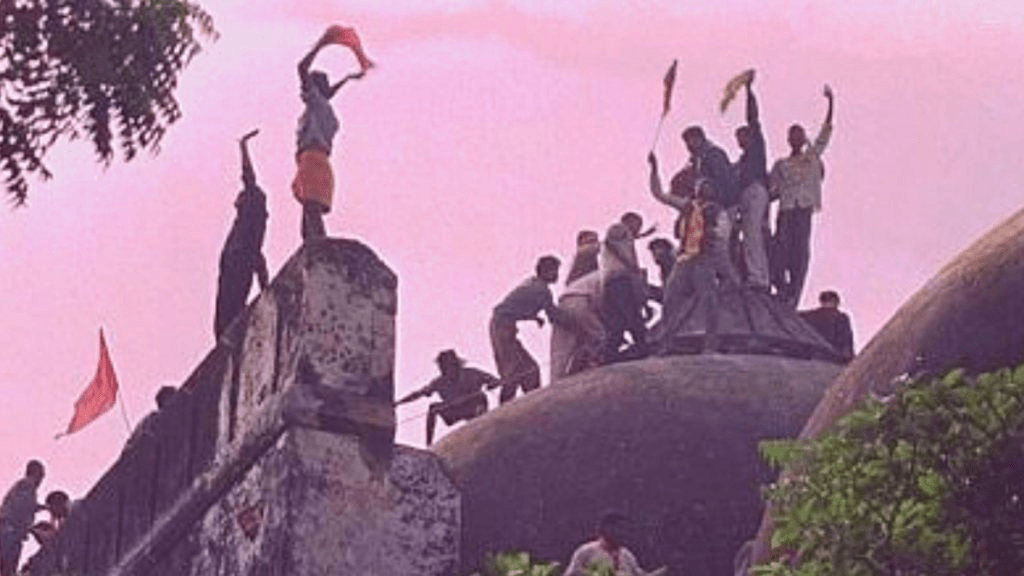

Of the Janata period, the book deals with what was happening inf the Morarji Desai government in those crucial 28 months from 1977 to 1979. The three top guns in the government _ Morarji Desai, Jagajivan Ram and Charan Singh could not get on well together and Charan Singh pulled the rug and brought down the Ministry. Years later, Morarji told me, “but for him (Charan Singh) the government would not have fallen.” Probably he was right; it is unlikely that Jagajivan Ram would have upset the apple cart. A new nugget of this period which appears in the book is that R.K. Dhawan, Indira Gandhi`s ever loyal Personal Secretary, was willing to turn approver before the Shah Commission of inquiry into the Emergency excesses and had contacted the Janata MP Krishan Kant (later Vice President of India) in this context; it was Kant who disabused him of the idea. On the Rajiv Gandhi administration, the author reveals that Sonia Gandhi herself was unconvinced about the Muslim Women`s Bill after the Shah Bano Judgment which was followed by the opening of the locks of the Babri Masjid at Ayodhya, a decision unleashed a chain of events culminating in the destruction of the Babri Masjid on December 6, 1992. Rajiv Gandhi`s Prime Ministership is given it`s due in the book. The Bofors issue, which ultimately brought about the demise of his government in the 1989 elections, occupies a good part of the portion on Rajiv Gandhi who was described as “Mr. Clean” and later “Mr. Whitewash” in that era! However, the book could have also spared some space to the anti-defection law which Rajiv Gandhi enacted and remains contentious even today.

The V.P. Singh regime of 11 months also comes in the chronological order of politics in the volume. The twin problems of Mandal and Mandir, which defined his rule, are covered adequately. As is well known, he decided to implement the Mandal Commission report as a reaction to the threat from the Haryana strongman Devi Lal. Chowdury also traces V.P Singh`s rise to the top job, his “raid raj” as Finance Minister, his shift to the Defence Ministry and his final bid for the top job at the hustings in 1989. He was the only leader to leave the Congress and become Prime Minister in about two years.

Another Prime Minister who occupies substantial space in this work is P.V. Narashima Rao who is described as “The Prime Minister Who Refused to Decide”, an echo of Rao`s well known statement that “not taking a decision is itself a decision” The part on him focuses mainly on the demolition of the Babri Masjid, which was a major event during his Prime Ministership; but the economic liberalisation and other aspects like ending terrorism in Punjab which took place in those years could have had more space.

On Atal Behari Vajpayee, Chowdhury gives a ring side view of his decision to conduct a nuclear test on May 11, 1998. Narashima Rao had backed down on the nuclear decison at the last minute in the winter of 1995, but Vajpayee went ahead mostly because it was something the BJP was committed to. However, he himself had been a peacenik in 1979 as External Affairs Minister! This was when the then Prime Minister Morarji Desai had called a meeting of the Cabinet Committee on Political Affairs to discuss a report by defence expert K. Subrahmanyam to the effect that Pakistan “was only a screwdriver away from the bomb.” Vajpayee had then supported Desai in his contention that India should refrain from going nuclear. This a scoop in the book. Later, Desai told the Chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission Homi Sethna: “As long as I am Prime Minister I will never permit an experiment”. We were still in the era of the Gandhian ideology.

The book mentions the oft-repeated quote that Nehru introduced Vajpayee to Soviet strongman Nikita Krushchev as “India`s future Prime Minister”. However, it must be borne in mind that this has recently been refuted by Vajpayee`s biographer Abhishek Choudhary who has written a serious work on the late BJP Prime Minister. The writer covers most of the main aspects of Vajpayee`s tenure at the helm and, at a personal level, his relationship with Rajkumari Kaul.

Manmomhan Singh`s Prime Ministership goes through Chowdhury`s X-ray as well and he emerges without much criticism. His role in as Finance Minister in Narashima Rao`s Cabinet and the economic liberalisation of 1991 is given its due as also the fact that Narasimha Rao`s first choice was former Reserve Bank Governor I.G. Patel for the Finance Ministry. It transpires that R. Venkataraman, the then President, suggested both I.G. Patel and Manmohan Singh as Finance Minister probables and then when Patel declined the offer, Manmohan Singh was the obvious choice. Also highlighted is Manmohan Singh`s strong stand on the Indo-U.S. civil nuclear deal when he openly made a statement against the Left, which was threatening to withdraw support if his government went ahead with the deal; the book records the developments leading up to Manmohan Singh winning the vote of confidence on July 22, 2008, despite the Left parties’ withdrawal of support. While the books gives Manmohan Singh a thumbs up for his job as Prime Minister she concedes that during his tenurt the high office’s image took a beating owing to the perceived role of 10 Janpath in decision-making. The book does not cover the present Prime Minister Narendra Modi as Chowdhury feels he is still “a work in progress” but in the epilogue she compares him to Indira Gandhi on one aspect: building of a personality cult. But the comparison ends there.

Apart from the few errors, Neerja Chowdhury has done a seminal work about the politics and lives of the Prime Ministers she has covered. It is a book worthy of a journalist of standing, which she is.